It was nearly fifteen years before Walter Johnson set foot on California soil again. Although it hadn't been planned that way, the timing of his return couldn't have been more glorious. He was a World Champion, and the country was still amazed over his resurrection and vindication in the astonishing final game of the 1924 World Series just a few weeks before. Johnson wasn't supposed to play in any ballgames on his trip to the coast; he was there to buy a baseball team. But when word got around, the inevitable proposals for exhibition appearances came in, and he agreed to three of them.

It had started quietly enough. In early 1924, Johnson was approached about buying the Vernon franchise of the Pacific Coast League. When the story leaked that he was seriously considering ownership of a team on the coast, he was contacted by Oakland of the P.C.L., and preliminary talks began. Walter had struck up a friendship with George Weiss, the savvy 28 year-old owner of the New Haven team in the Eastern League (probably through Clyde Milan, the New Haven manager). They decided to go after a Coast League team together, Johnson putting up part of the money and Weiss arranging for additional financing. Weiss was to run the team's business affairs, Walter to manage and pitch. He announced that 1924 would be his last year in the major leagues, and immediately following it he would go out to the west coast to buy a team.

Actually, Johnson had been back in California briefly, early in 1923. Walter, his wife Hazel, and their children had been visiting her father, E. E. Roberts, the mayor of Reno, Nevada, when one-year-old Bobby became seriously ill and had to be taken to Children's Hospital in San Francisco. There were two operations, and Walter stayed in the city for several weeks as Bobby struggled to survive. (Hazel remained in Reno nursing Carolyn, born two weeks before.) One of the few cheerful events during this dark period was a reunion with his first big-league manager, Joe Cantillon, also in San Francisco.

Now, almost two years later, Johnson was in California again, under much happier circumstances this time, and looking to make it his permanent home. Arriving in Los Angeles on October 25 after a brief visit to Coffeyville, his stay in California attracted constant media attention, starting with an invitation to the studios of radio station KHJ to appear on a talk show hosted by "Uncle John". Walter had agreed to play in three exhibition games, the first in Los Angeles on October 26. He was paid $1,000 plus expenses to pitch for the White King Soap Company team, which consisted mostly of players from the Los Angeles Angels, against the Vernon Tigers. A Sunday crowd of 20,000 jammed into the old Chutes Park, now called Washington Park and in its last days as a baseball field before the opening of Wrigley Field in 1925. Before the game, E. L. Doheny (whose trial in the Teapot Dome scandal had been postponed so he could attend the game) came onto the field to a big ovation, and Walter came out to greet him. They chatted about Frank Johnson working for Doheny on the Santa Fe oil lease, then Walter pitched the "first ball" to Doheny and autographed it for charity. Doheny immediately bought the ball for $500, and they both signed one which auctioned for $100. Walter autographed 50 balls for charity, and was presented in return a ball autographed by 50 Hollywood movie stars.

As for the game itself, the huge crowd got what it came to see -- a masterful performance by Walter Johnson. At the end of six innings, Vernon had one safety, and to start the seventh Walter let up enough to allow two clean singles. But seven pitches later, a pop-up and two strikeouts had ended the rally when, as one newspaper reported, "his speed became so great that batters swung at the sphere after it was safely in the catcher's mitt. Johnson was taken out so that the Coast League sluggers might have a chance." In seven innings, Walter gave up three hits and one walk, struck out seven, and left with a 1-0 lead. His relief didn't fare as well, Vernon coming back for a 5-1 victory. "Joe Jenkins (the Soap Kings' catcher), who caught Johnson in 1912, informs the world that Big Walter had just as much stuff yesterday as he had a dozen years ago," the paper continued, "Jenkins' swollen hand is mute testimony to the blinding speed of the great Walter. Chester Chadbourne, who has as good an eye as there is in the league, admitted that Johnson whipped a third strike over on him that he never even saw after it left the pitcher's fist."

Walter went from Los Angeles to the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, and Hazel came over from Reno to join him. This was something of a homecoming for Hazel, too, who was born and spent her first several years in nearby Hollister, California. Her parents were both natives of the state, her father's parents original "Forty-Niners", arriving from the Midwest during the Gold Rush. Growing up in Carson City, Nevada, Hazel had made the trip over the Sierras into neighboring California many times, especially to visit her cousins. With her roots and family there, Hazel looked forward to the prospect of taking up residence on the Coast.

But first, business had to be taken care of, and that started in Oakland on the morning of October 28 with a preliminary meeting at the Central National Bank with Cal Ewing, owner of the Oakland Oaks P.C.L. team, and J. F. Carlson, the bank's president. The next day a luncheon in Walter's honor was given by the Oakland Chamber of Commerce at the Oakland Press Club, followed by an exhibition between "Devine's Major League All-Stars" and Walter (Duster) Mails' "Coast League All-Stars" at the Oakland ballpark. The big leaguers blanked the minor leaguers, 2-0, as Walter Johnson went the first five innings for the Devines, allowing two hits. The game had been touted as an opportunity for Oakland fandom to show Johnson their enthusiasm for the game. But when just 2,000 of them braved a chilly drizzle, the local press pronounced it a big flop instead.

Walter and Hazel headed south, stopping in Santa Monica to visit his grandparents, then on to Orange County where a homecoming fit for a returning hero had been planned. Just a few days earlier, Walter's thousands of friends and fans in the county had crowded the streets around local newspaper offices to watch giant electric scoreboards, or huddled around primitive "crystal sets", anxiously awaiting the results of World Series games. Now they would have a chance to see their hero close up, first in a grand parade, then pitching in a contest that would resemble more a carnival than a baseball game.

A dozen of Walter Johnson's teammates from the Olinda days were assembled for a grand reunion dinner October 30 at the Anaheim Elks Club: Joe Burke was now the District Attorney of Los Angeles; Guy Meats, a wealthy citrus farmer; Bob Isbell had stayed in Olinda, presumably still playing violin at the Saturday night dances; Clair Head and Anson Mott came over from Garden Grove, and Joe Wagner and Johnny Tuffree from Placentia; Faye Lewis was now a prominent Anaheim attorney. Only Billy Elwell, still in Weiser, and Jack Burnett, who had disappeared, were missing from the Oil Wells of the old days. The ballplayers were the featured attraction of the Anaheim Merchants and Manufacturers Association's parade that evening, with Walter Johnson -- the Grand Marshal -- leading a procession of seventy floats with brass bands at either end. This was the first in a series of Halloween parades that took place every year until the city of Anaheim withdrew its financial support after the 1991 event.

Riding with Walter in the first car was none other than Babe Ruth, who was on the Coast with his barnstorming troupe. Walter's Olinda teammate, Faye Lewis, who was the Exalted Ruler of the Elks club (the Meusel brothers were also members), had worked hard to get Johnson and Ruth together for a big charity game. Arrangements were made to squeeze it in before Commissioner Landis's November 1 deadline for the cessation of all exhibition activity for major leaguers. At the last minute, Lewis had succeeded in getting Ruth and Johnson to take part in the Halloween parade as well. Tonight, with Walter's old teammates filling out the first two cars, they waved to the crowds lining the streets of Anaheim. The Gazette described the holiday atmosphere pervading the event:

"Thousands of people from all sections of the country congested the streets of Anaheim to witness the Halloween pageant and take part in the street dance. A large percentage of the people who thronged the streets were clothed in masquerade costumes. Witches and their black cat symbols were numerous, a few horned and tailed devils mingled with the crowd, and the ubiquitous small boy with his horn or other noise-making apparatus was out in full force. It was a joyous and fun-making crowd, everybody demanding the right to do as he darned pleased and conceding the same privilege to everybody else. As soon as the parade broke up, dancing began on the Center Street [now Lincoln Avenue] pavement between Los Angeles [now Anaheim Blvd.] and Lemon streets, and the merry dancing was kept up until midnight."

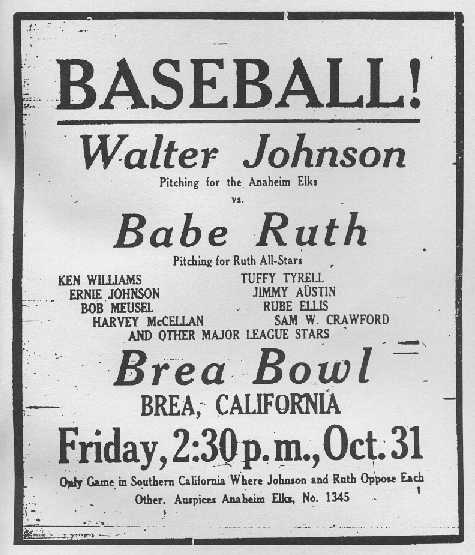

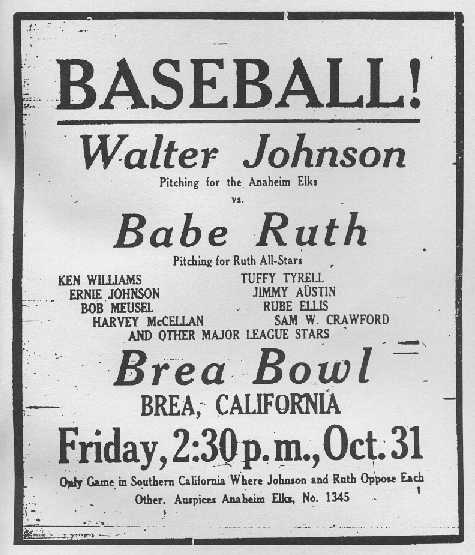

The big game -- Walter Johnson's last in California, as it turned out -- took place the next day.1 Appropriately enough, it was one that would be talked of and written about in the area for years. The location chosen was the Brea Bowl, a natural amphitheatre near the corner of Brea Boulevard and Birch Street, maintained by the Union Oil Company for its semipro baseball team and within shouting distance of the Olinda flat where Walter got his start. Businesses in the vicinity closed at noon, and the holiday mood was still in effect. This was truly a community celebration, as the Fullerton High School band played, the American Legion post provided security, the Boy Scouts directed traffic, and local church women sold refreshments. Cars began streaming in early to Brea, and by game time on a beautiful fall day a crowd of 15,000 or so had packed the hills around the ballfield.

Johnson's pitching was not, sadly, one of the more memorable features of the game. After a tough pennant race, three games in seven days in the world series, and nonstop exhibitions since, his arm was not up to this final effort. If he had been facing minor leaguers, as in the games earlier that week, he might have fared better. But instead, he was pitching to Babe Ruth and a lineup of past and present major leaguers. In his five innings on the mound, Johnson gave up eight runs on eight hits -- four of them homers, two by Ruth (the second estimated in all newspaper reports at 550 feet) and one by Sam Crawford. He did ring up six strikeouts, finally getting the Babe the last time he faced him.

The pitching star of this game was not Walter Johnson, but -- Babe Ruth. In his first mound appearance in more than three years, the former premier lefthander of the American League carried a shutout into the ninth inning, when he grooved a gopher ball to his teammate and friend, Bob Meusel. Ruth gave up six hits total in a 12-1 complete-game win over a talented lineup that included Meusel, Ken Williams and Jimmy Austin of the Browns, Donie Bush, and Johnson (who set the batting mark for pitchers, .433, the next year). W. E. Griffith, still living in Brea 45 years later, related an incident from the game that sounds straight out of the "The Babe Ruth Story": "I remember Babe Ruth hit a foul ball that bounced off a car and hit a boy in the head. He started bawlin' and Ruth walked over to him, handed him a silver dollar and said, 'Don't cry, kid -- here.'"

In addition to being overworked, Johnson was also handicapped by his catcher, Forrest B. "Bus" Callan of Anaheim, who had caught at Fullerton High a few years earlier and now caught for the Union Oil team on weekends. Callan recalled the occasion more than 50 years later:

"I used to be a pretty good catcher, but I was rusty by then. Honestly, when he threw in some of those fireballs, I couldn't see them. We had a short conference at a spot between home plate and the pitcher's mound, and I said, 'Walter, I just can't see the ball.' He replied, 'Just put your mitt where you want me to throw and I'll throw into it', and he did! Since I couldn't see the fast balls coming, I couldn't jerk my mitt back as one does to ease the shock in catching them. I got a beautifully sprained wrist." They had another talk when Babe Ruth came up the first time. Callan said Johnson told him, "Bus, the crowd wants to see Babe make some home runs and we don't want to disappoint them. The first two times I'll throw him a couple of easy ones that he can't miss." Another one of the five Anaheim boys playing behind Johnson in the game was Vic Ruedy, in centerfield. Ruedy became the parks superintendent for the city of Anaheim, and it was under his jurisdiction that Anaheim Stadium, home of the major league Angels, opened in 1966.

The day after the Brea Bowl game, Walter returned to the Olinda oil fields to call on his many friends from times past. Then the Johnsons spent a few days sightseeing around Los Angeles. Douglas Fairbanks gave Walter and Babe Ruth a tour of the set of "Thief of Bagdad", his current hit movie. Other studios opened their sets to the famous pitcher, and photographed him with the casts of films in production. Johnson, with movie-star looks of his own, could easily pass as the leading man in these publicity shots. There was a momentary scare when Hazel suffered an appendicitis attack and checked briefly into St. Vincent's Hospital, but it was not acute and she was released. After several weeks vacationing in California, they returned to Reno.

George Weiss, in the meantime, had been trying to complete the deal for the Oakland ballclub. A media circus had been created by Walter Johnson's visit to the west coast after his stirring series victory, and the papers were treating it as a foregone conclusion that he would buy a team and make his home there. Cal Ewing tried to take advantage of Johnson's declared intention of buying the Oakland club to raise the price from his first quote of $265,000, and Weiss was having trouble convincing their financial backers to go along. The Oaks had been the laughingstocks of the Coast League for years, and the league itself was not doing well, with only San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle turning a profit. Ewing's new asking price, $385,000, was actually $10,000 more than was recently paid for the major league St. Louis Cardinals.

It was big news around the country, and headlines on the coasts, when Ewing announced on November 18 that Walter Johnson and George Weiss had bought the Oakland ballclub. The announcement was premature, however, and just a few days later the deal had fallen through completely. Weiss returned to New Haven in disgust over Ewing's shenanigans, and Johnson went for a long hunting trip in the mountains around Reno. The other Coast League owners were furious with the Oakland owner. G. A. Putnam of the San Francisco Seals suggested publicly that the seven other P.C.L. clubs establish a fund to help Johnson buy the Oaks. "The money that we give Johnson will be the best investment we ever made," Putnam said, figuring that the fund would repay itself through increased interest and attendance from his presence in the league.

Johnson had one last meeting with Ewing in Oakland, three days into the new year of 1925, but nothing came of it. He went from there to Los Angeles to see Ed Maier, owner of the Vernon team, at his home on Catalina Island. It was Maier's club that had sparked Johnson's interest in the first place, and he was still willing to sell at a price acceptable to Johnson and Weiss (who had come back to the coast). But first a situation had to be settled that threatened to make Vernon an undesirable franchise at any price. Maier and William Wrigley, Jr., owner of the Los Angeles Angels, had been locked in a bitter feud for some time. Wrigley had even announced that it was his intention to force the Vernon club out of business, or at least out of Los Angeles. Apparently, this had been a factor behind the construction of Wrigley's new ballpark, due to open this year (and off limits to the Vernon Tigers). Wrigley told Johnson he was going to bring the Salt Lake P.C.L. club into Long Beach to play their home games at his new stadium, and would make no deal for Vernon to play there regardless of who owned the team.

On January 29, 1925, a discouraged Walter Johnson left Los Angeles for Reno to pick up his family for the trip back to Washington. He would not return to California. What should have been a winter spent basking in the glow of his championship season had been devoted instead to chasing elusive dreams of ownership. "It only took the diseased Coast League political organ a few weeks to fill his cup with wormwood," is how one Los Angeles paper put it. Tom Laird, sports editor of the San Francisco Daily News, railed at the P.C.L. powers for letting Walter slip away: "Those responsible for the predicament in which Johnson has found himself should be proud. The assuming of a thumbs-down attitude against Johnson is the biggest mistake of their careers. Johnson would have added the color and prestige to the Coast League that it lacks, and always will lack, until men of his caliber are part and parcel of it. The Coast League needed Johnson, but Johnson does not need the Coast League!"

1 In October 2006, a narrated slide show including several photographs taken at the Brea game was made available at the YouTube video sharing site. We highly recommend it!

| Previous | Intro | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Epilogue | Stats | Next |

| Idaho article |