The esteem in which Johnson was held by Washington fans was symbolized by the trophy he won as the most popular Nationals player, with a total of 141,000 votes, which Frank Johnson put on display in the window of Stern and Goodman's department store in Fullerton after the 1908 season. The same high regard and adulation carried over into the next two winter league seasons. Walter's appearances were well documented in the local press, which referred with pride to his growing stature as a major league pitching star, as well as to his Orange County origins.

For the 1908-09 season of the California Winter League, Hawley Park had a new grandstand and bleachers. The expansion was financed with a general admission of 25 cents, 10 cents extra for the grandstand (to which ladies were admitted free). Santa Ana also had new uniforms, solid green with yellow stripes on the socks, bringing them a new nickname, the "Yellow Sox". This edition of the league was down to ten teams, losing Santa Monica, Santa Barbara, Dolgeville, and two of the L.A. clubs, but picking up Azusa, San Diego, and the Salt Lake Railway's locally-based team.

Before starting his second winter season with Santa Ana, Johnson pitched on October 18 for Olive against the Los Angeles Giants, a powerful club that had lost only one of 35 games to date. The Los Angeles Herald called the Giants "the champion colored team," and this was the first of only a handful of games Johnson pitched against black teams in his career. He lost an 11-inning thriller, 6-5, despite striking out 20 Giants. Guy Meats, probably hurt, played first base and a "new catcher", Collins (Grover?), was behind the plate. Collins made three of Olive's six errors and allowed four stolen bases to contribute to the defeat. Hunt and Clark (no first names given) pitched for Los Angeles and struck out 14 Olives.

As the Herald reported several weeks later, "The Giants stock was given a big boost when they won from the Orange Athletic Club [Olive] with Walter Johnson, the famous pitcher of the Washington American League club, twirling against them." The San Diego Pickwicks set up a four-game series with the Giants, and the (again) P.C.L. champion Los Angeles Angels challenged them to a game. This contest, on November 8, 1908, drew a crowd of 5,000, half of it "colored". The Angels lineup was fortified with some of the better players from the Coast League, but it was their own Dillon, Gray and Brashear hitting home runs in a 14-2 rout of the "heretofore invincible Giants, the pride of darktown," as the Herald called them.

The Santa Ana Register reported that Johnson was "not in the best of shape ... not feeling well ... " in his league opener a week later. Although he fanned 15, Walter took his worst winter beating ever, giving up six earned runs on 13 hits in an 11-3 loss to Pasadena. It wasn't specified what ailed him this time, but he missed the next two games. He came back strong, however, on November 15 with a 2-hit, 20-strikeout win over the Edisons, and again the next week, a 10-inning, 2-hit, 0-0 tie with Salt Lake. Although he finished the season with two solid shutouts -- letting the Pickwicks down with two hits on February 22, 11-0 (avenging two earlier losses to them), and five days later striking out 15 Hoegees in a 2-0 4-hitter -- this winter season wasn't one of Johnson's best. He won seven games and lost five, averaging 2.7 total runs, 4.5 hits, 1.7 walks, and 10.1 strikeouts per nine-inning game -- good numbers, but not for Walter Johnson. As a batter, his average slipped to .244. The winter league seasons proved to be a reliable forecaster of his summer big-league fortunes, with this one no exception.

In late September 1909, toward the end of his worst-ever season at Washington (13-25), Walter wrote Ed Crolic, assuring the Santa Ana manager that his arm was "fine" and he would be back for another winter league season. Johnson had sustained a sore arm (one of two in his big-league career -- it would be eleven years until the next one), sitting out most of September. Crolic's concern was prompted no doubt by sensationalized (and widely circulated) reports that Johnson's injury was career-ending. Although there had been grave concern the first day or two when Walter couldn't raise his arm over his head, he came back after a three week rest with a complete-game shutout of the perennial American League champion Detroit Tigers.

If Johnson had had any concern about his arm, moreover, he wouldn't have signed on with Connie Mack's ambitious post-season barnstorming tour. Mack's Philadelphia Athletics, with the "$100,000 infield" and Plank and Bender, were nosed out by the Tigers for the American League pennant. Now, for the next two months, they were to play the "All-Nationals" -- Marquard, Meyers, Snodgrass and Doyle from the Giants, Johnson and Dolly Gray from the Senators, Rube Ellis from the Cardinals, and others. A 50-game loop through the West, starting in Chicago and ending in New Orleans, was scheduled. Many of the "All-Nationals" were California natives from both leagues looking to pick up extra money as they made their way home for the winter.

Walter hooked up with the tour in Seattle on October 27, losing to the A's, 5-3. Chief Meyers, following his first year as Christy Mathewson's favorite batterymate, caught Johnson in this game. (Fred Snodgrass caught him the rest of the tour.) The teams then split up, the All-Nationals heading south to San Francisco where Johnson pitched a pair of victories against the P.C.L. Seals, the last a 7-0 blanking the day after his 22nd birthday. They continued down to Los Angeles, where Walter won two more games against the L.A. Angels. For both games, the Los Angeles Herald reported, Chutes Park was "well packed to see players whose faces were once familiar on local diamonds again playing before Los Angeles fandom and with big league company." The second contest, on November 14, was billed by the Herald as a homecoming for Johnson: "Sunday will be Johnson Day at Chutes Park. The wonderful Washington-American twirler will be greeted not only by a large delegation of fans from Fullerton, his home town, but in all probability by every devotee of the game who remembers Walter as a busher."

The big-leaguers met up again for several weeks of exhibitions in the Bay area, with Johnson beating the A's twice in San Francisco and playing centerfield in Stockton. Moving south for its final leg on the coast, the tour, plagued by bad weather from start to finish, was washed out in Santa Barbara and San Diego. But in Los Angeles on December 12, the clouds cleared long enough for the last game before the California natives dropped off and the rest headed into the southwest. The Herald advertised it as "the first contest between major league teams ever played in Los Angeles ... it is expected that a strong array of Fullerton fans will occupy seats today to see their townsman, Walter Johnson, perform." Although he pitched well, Johnson was beaten, 4-3, with all the A's runs coming in the eighth inning, three of them on errors.

Johnson won six games and lost three on the tour. He took all four of his games against the P.C.L. clubs, but had more trouble with the powerful A's, the World Champions in 1910 and winners of four of the next five American League pennants. The once-ambitious tour ended in a downpour in New Orleans a week later, after being snowed out in El Paso and rained out in San Antonio and Houston. It had been a dismal failure, with only half of the 50 games getting played -- some of those to empty stands -- and the rest cancelled for rain, snow, or cold. According to the players, it would have been much worse without the capable management of Frank Bancroft with the All-Nationals and Connie Mack for the A's.

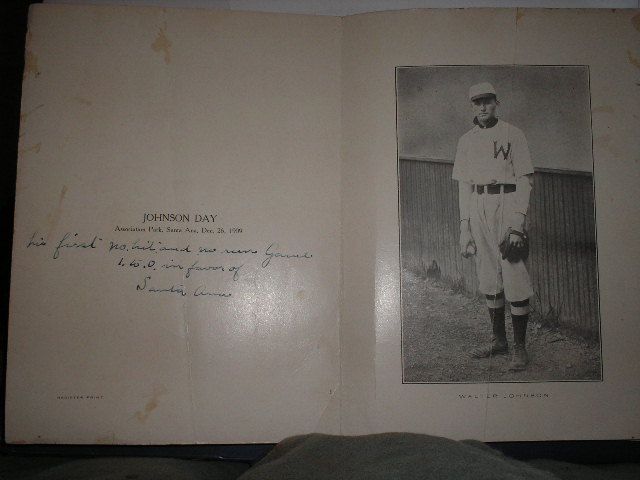

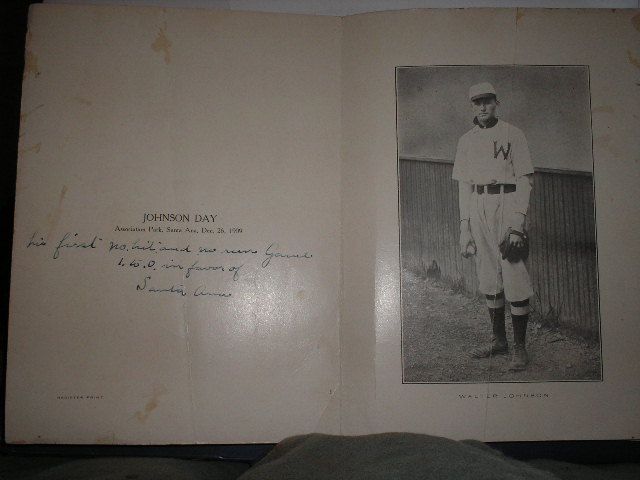

The California Winter League was well under way by now, and Johnson joined up with Santa Ana for the third time -- and his final season of baseball on the coast. Taking advantage of the publicity surrounding the recent barnstorming games, the Yellow Sox made December 26 "Johnson Day" at Hawley Park. "The greatest turnout in Orange County's baseball history is expected," enthused the Santa Ana Evening Blade," as every prominent man in baseball circles has been invited and also all the reporting writers of the Los Angeles papers are expected to be present. Ed Crolic, manager of the club, has had 2,000 portraits1 of Johnson made and every patron of the game will receive one free." It certainly was Walter's day in every respect, as he delighted the large crowd with a no-hit game against Salt Lake. The Blade, unembarrassed by exaggeration, called the 15-strikeout performance, "the most phenomenal feat ever to have taken place in Santa Ana. Johnson Day was a grand success," they continued, "and the fans cheered when they heard the good news that the Olinda boy will be in the lineup all season ... The high position he holds in the baseball world has not in any way affected his genial disposition."

Shortly after the start of the New Year of 1910, the Yellow Sox were strengthened by the addition of Rube Ellis and a big second baseman named "Chick" Gandil, who had been playing earlier in the winter in the cutthroat Imperial Valley League and who now worked at Ed Crolic's Fourth Street pool hall as a "house man" (where he might have picked up the habits that landed him in baseball's Hall of Shame). With Gandil and Ellis batting 3-4 in the lineup, and with Walter Johnson on the mound, it's hard to see how Santa Ana could ever lose a game -- and they didn't. Johnson had a perfect 9-0 record this winter, with four shutouts and four 15-strikeout games, including one against each of the Salt Lake Railway teams -- the "colored" Occidentals and the white nine, usually referred to as "Salt Lake". He allowed a total of only 5 runs, 21 hits, and 3 walks in nine complete games, and struck out 112 batters. The new Washington manager, Jimmy McAleer, was on the coast and saw Johnson one-hit the McCormicks on January 9. McAleer, as manager of the St. Louis Browns, had seen Johnson for three years in the American League and wouldn't have been surprised by his mastery over semipros. But if he had known how accurately these short winter league seasons forecast the following summers, McAleer would have been thrilled. Johnson was about to turn his 25 losses in 1909 into 25 wins in 1910, the first of ten 20-victory seasons in a row.

On March 9, 1910, the Fullerton Tribune noted that "Mr. and Mrs. F. E. Johnson, accompanied by their son, Walter, left for Coffeyville, Kansas." Frank Johnson had just returned from a trip there to buy a farm, and now his family was moving back to Kansas, permanently. Walter had never gotten completely used to the constant climate of Southern California, and development in the Olinda Oil Fields was taking place at a furious pace -- the Santa Fe lease alone had produced 1,100,000 barrels of oil in the past year. Mostly, though, both Walter and his father wanted to be Kansas farmers again. And now, after three years of major-league salaries, he was in a position to do something about it. They were leaving behind many relatives, including Walter's grandparents, John and Lucinda Perry, who remained in Southern California the rest of their lives, and all of his Perry aunts and uncles. In fact, a large number of Walter Johnson's relatives are undoubtedly living in Southern California today.

1 Here is one of the photographs which were distributed on Johnson Day. It turned up at an estate sale in Kansas in 2006:

| Previous | Intro | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Epilogue | Stats | Next |

| Idaho article |