A result of this impromptu tryout may have been Walter Johnson's appearance in the Oil Wells' 21-to-6 rout of the "Eureka" team which took place on July 24, 1904. The Fullerton Tribune reported that "Johnson, the crack pitcher of the Olinda 'kid' team, fanned six men in the three innings which he pitched." Whether the 16-year-old pitcher allowed any of the Eurekas' runs is not known.

In 1939, Bob Guild recalled a game which could easily

have been the one reported in the Tribune. It involved the

Olinda Oil Wells, who "were playing a pickup team from Los Angeles on

a dusty Sunday. Horses and buggies, surreys and carryalls lined the

Anaheim ball park, out where the Santa Fe station now stands. Several

hundred rabid fans lined the sides of the playing field, cheering for

their team from the oil fields. It was no match, however. Those Olinda

giants were slapping the ball all over the field. The score mounted and

mounted.

"Finally, the score one-sided and a foregone

conclusion, Joe Burke, now one of Los Angeles' better known attorneys,

waved to a lanky grammar school kid standing near home plate. 'Go on in

Walt,' he said. 'Let's see what you can do.' And that's where Walter

Johnson, the Big Train of professional baseball, got his start -- the

start that saw him launched on one of the greatest professional baseball

careers the game has ever seen.

"Because lanky Walt handcuffed the Los Angeles gang,

with the aid of his old batterymate from Olinda Grammar School, a lad

named Collins, now almost forgotten. Later in the same game, Ted Craig,

who later became speaker of the state assembly, and who was a schoolmate

of Johnson's, got in the same game on first base.

"'Chili' Fisher, now an Anaheim service station

proprietor, was scorekeeper for the game, and vouches for the story as

the real lowdown on the Big Train's start..."

No record of any other appearance with the adult Olinda Oil Wells team during 1904 exists -- Frank Johnson may not have wanted to see Walter try to do too much too soon. in any event, Olinda manager Tom Young had all the pitching he needed between Art Crips and Rube Crandall. by the beginning of 1905, however, the now 17-year-old Johnson was finished with the boys' games on the flat. His last game with them might have been on January 22, when the Fullerton Tribune noted that the "Olinda school team" (most likely the boys team) beat a "picked team 8-5 on the local diamond." One impetus for Johnson's joining the adult Olinda nine may have been the defection of Rube Crandall. It was reported in the January 5 Anaheim Gazette that "Jasper Crandall, the oil men's change pitcher, has gone to San Pedro and will henceforth wear a seaside uniform. Crandall is a good one, and fans hereabouts are sorry to note his departure..."

On February 2 the Tribune broke the news that "Walter Johnson and Grover Collins have been added to the list of professional players for the famous Olinda team." Johnson later wrote that he asked Tom Young if he could pitch for the team. But whether he did the asking, or they asked him to join on the strength of his session with Burke and Burnett, by the time the Tribune reported his addition to the Olinda roster he had already started his first game for the Oil Wells -- an 11-inning, complete game at that.

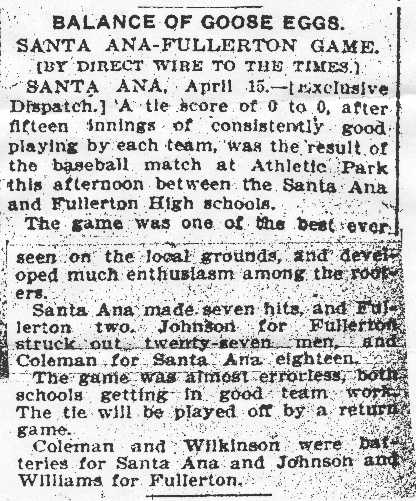

Barely 17 years old (his birthday was November 6) and a freshman in high school, Walter Johnson started his first organized game on January 29, 1905. On that day, the Oil Wells took on the Rivera nine on their home grounds at Los Nietos, next to the railroad tracks just west of Whittier. Olinda infielder Lafayette A. "Faye" Lewis later remembered that "at that time the Rivera bunch was one of the strongest in Southern California, and the Olinda team was much broken up because the regular pitcher, Art Crips, would be unable to pitch that game. Walter Johnson, just a kid at that time, was brought out to pitch for us that day. The players on our team considered there was no chance of winning and instead of getting in and backing the kid up, as they should have, played a terrible fielding game, making at least nine or ten errors." Although acquitting himself well in this first performance, he lost the game, 5 to 4. Rivera's Rube Ellis, later an outfielder for four years with the St. Louis Cardinals, smashed a two-run home run in the bottom of the eleventh inning to break a 4-4 tie. (According to scoring rules of the day, only the winning run counted.) Johnson allowed nine hits and struck out eight. Bases on balls weren't given, but he did hit a batter. The Whittier News observed that the loss broke a 29-game win streak for the Olindas (a slight exaggeration!), but it also gave their "young twirler" his first good review: "Johnson was presented as a high school kid," it said, "but he is certainly a graduate in the science of delivering the ball."

Rivera's lineup1 also included a 17 year old student destined for fame in the big leagues -- Fred Snodgrass, their catcher, three weeks older than Walter and a senior at Los Angeles High School. John Tuffree, who played for the Oil Wells several years before, witnessed this game and many years later recalled his impression of Johnson in his first game:

"There was no uniform for him to wear, so they gathered some odds and ends. Always a husky youth, the shirt he wore was too short, so his shirttail was out after every pitch and his pants hit him well above the knees. They were too tight to buckle and his cap bobbed on his head. He took an awful ribbing, which he ignored, fanned every batter, and before he was through he had the entire crowd cheering for him." The Whittier News reporter didn't notice the pitcher's appearance, but commented that "the Oil Men looked very dangerous in their bright scarlet suits, and went to bat with every expression of confidence."

Walter had entered Fullerton Union High School in the fall of 1904 as a freshman (ninth grade). Why he fell behind two years in school in California -- he finished the eighth grade on schedule in Kansas -- is a mystery. The California schools were possibly more advanced, and his education handicapped by the tiny (22 students for six grades) Kansas country school. He stayed on track in the much larger Humboldt City School, however, and was a conscientious student -- listed in the Humboldt Union for perfect attendance in two of his first three months of the eighth grade.

Johnson's next appearance of record was February 18th, pitching in relief for Fullerton Union in a 7-3 loss to Norwalk High. The only details given were the batteries (Charles Hansen, Fullerton's captain, started the game; Collins was the catcher). Fullerton's baseball team had no coach and no formal league, but had been competing against other suburban Southern California teams for several years. In 1902, they had won a cup emblematic of the "Southern California Interscholastic championship", but by the Fall of 1904 their fortunes were at a low ebb. The school had been founded in 1893, and in 1905 there were only 13 graduating seniors, and 60 students in all four grades. This was also the first year for the school yearbook, "The Lucky Thirteen", and it describes how the team was organized in November, 1904, with an allotment from the school board of "25 dollars plus two-thirds of the walnut crop" to sell for equipment. The season was said to have begun in February, and it's not clear whether Johnson was practicing with the team before he hooked on with Olinda, or if his "professional" career was already underway.

Hollis Knowlton, an outfielder for the high school, took credit many years later for getting Walter a tryout for pitcher with Fullerton Union:

"I had played against him when I was playing for the Fullerton town (boys) team the year before, in 1904," Knowlton said. "I can remember he played catcher with no mask and played about 10 feet behind the plate. I got on first and tried to steal once. He threw me out by 30 feet. So when ol' Walter enrolled at Fullerton the following year, I was the only one around who was aware of how hard he could throw a ball." Johnson, however, remembered first catching for the high school team. Unfortunately, the Fullerton Tribune didn't consider these contests newsworthy, and coverage is spotty. Johnson is mentioned as part of the battery in just two games, both as a pitcher.

The Anaheim Gazette did find the Oil Wells' games worthy of mention, and Johnson's continuing semipro career is a matter of record. On February 26, he was in rightfield in a 7-5 win over Downey, and a week later made his first pitching appearance on the "home" field at Athletic Park in Anaheim, with a large and enthusiastic crowd in attendance. Although giving up only four hits and one walk while striking out five of the Hoegees of L.A., he was the victim of five Olinda errors and lost again by the score of 5 to 4. In addition to a poor performance in the field, the Oil Wells wasted most of their thirteen hits against Hoegees pitching. But the Gazette didn't ignore the efforts of the young Olinda hurler, and even tagged Walter with his first nickname:

"Far and away the most pleasant feature of the game was 'Kid' Johnson's pitching for the Olinda team, this being his debut in fast company [not so]. He remained cool-headed throughout the game...Johnson is a good 'find' and he had a host of admirers upon his first appearance."

Rain washed out games for two weekends in a row, an occasional hazard of Southern California winter ball. Johnson's next game was probably at Fullerton High against undefeated Santa Ana High on April Fool's Day. In his memoirs, he recalled pitching both games of a two-game series against Santa Ana, and this was the first game of the pair. It was reported by the Santa Ana Evening Blade as a 3-0 loss, the unnamed Fullerton pitcher giving up nine hits. Unfortunately, the Fullerton Tribune has nothing on the game at all. Walter remembered (on two different occasions and several years apart) the game as 21-0, and this discrepancy, with the limited reporting, raises the possibility that these are different games. There is no doubt, though, that Walter was in the outfield for the Oil Wells the next day as they edged the Hoegees, 7-6. "Kid Johnson's left fielding was way up and he gathered in the sky-scrapers with neatness and dispatch," the Anaheim Gazette reported of his three catches.

A week later he was back on the mound for Olinda against the L.A. Owls. He pitched his best game yet, striking out eleven, but lost again, 5-2, as the Owls took advantage of his inexperience and that of a substitute third baseman. In the ninth inning of a 2-2 tie, the Owls bunted six times in a row, four for hits, and scored three runs. Still in his adolescence, Walter was the "awkwardest fellow on the team," in Joe Burke's assessment:

"Many a time I have seen Walt pitch a superb game, and along toward the last a little bunt would come rolling down to him gently, like a zephyr from the western sea. Walt would start to get it, his feet were sure to tangle and Walt was sure to fall down on the ground. Tall and angular, his feet and hands were abnormally big, out of proportion to the rest of him. He afterwards grew up to his extremities. While he handled himself like a barnyard animal in fielding and baserunning, he was always a good batter, and he had that graceful swing of the shoulders and free action with his arm. He sure could pitch."

Johnson's coordination problems weren't helped any by the teasing of his teammates, but he handled that better, according to Burke: "The oil wells bunch has no mercy on its friends, and boring into some fellow is a favorite pastime. Their joshing was rough-shod stuff, and Walt had a lot to take. He knew it and took his joshing like a man."

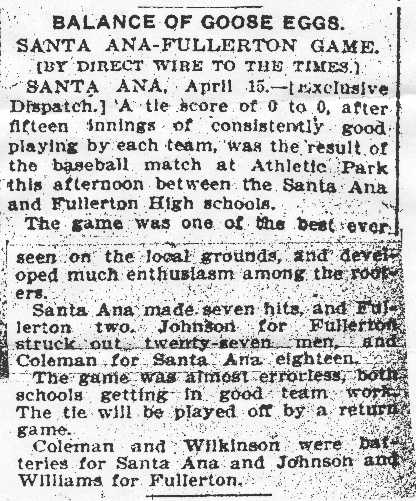

There would be no joshing to endure the following Saturday, April 15, however, as Johnson pitched one of the great games of his career. Even though the Tribune's coverage of Fullerton's high school team was meager, it was more than generous in reprinting bulletins from the Santa Ana Evening Blade on the successes of that city's powerful team and its invincible pitcher, George Coleman. The "Saints" had won every game played against other high schools, played the powerful Elks to a tie, and lost only to Occidental College. In typical performances, on February 25 Coleman set down Whittier High with an 11-inning 4-hitter, 2 to 1, and on March 25, George fanned 14 Riverside batters while winning a 6-hitter, 2-1. He had allowed Fullerton only 3 hits in the April 1 shutout, so there was little reason to expect George Coleman's pitching to be matched by the relatively unknown "Kid" Johnson.

But in a 15-inning, scoreless endurance contest against Santa Ana, Johnson struck out 27 batters -- his highest total ever. Santa Ana's ace rose to the occasion and allowed only three singles (one by Walter), one walk, and set down 17 on strikes, while Johnson gave up seven hits -- two of them doubles -- and walked three. "A Series of Goose Eggs," headlined the Blade's report on the game at Athletic Park on Fruit Street in Santa Ana. "Rooters were out in force for both sides and the grandstand was kept in a constant uproar applauding the brilliant work of the players." "The local boys," the paper judged, "showed decided superiority in fielding and teamwork, but could not connect safely at critical times." The Blade's partiality was vindicated several weeks later when Coleman pitched Santa Ana to the Southern California championship with a 1-0 15-strikeout one-hitter over Polytechnic High of L.A., followed by another one-hit 1-0 win over Los Angeles High. Tragically, George Coleman's promise was never realized in professional ball. After a brief stint with Los Angeles in 1908, his career was cut short by typhoid fever.

The Evening Blade reported that the game could have continued several innings more, and that's how Warren Hillyard, Santa Ana's shortstop and leadoff hitter, remembered it fifty years later:

"The game wasn't called because of darkness but because the officials decided it was too tough on the players, especially the pitchers. Furthermore, the rooters had long since lost their voices so it seemed useless to carry on any longer." Garland Ross, the Saints' captain and cleanup batter, recalled what it was like facing Johnson in this game:

"For the most part, we just went up to the plate, took our three swings, and walked back to the bench. I remember we all kept saying to the next batter, 'He ain't got a thing but a fast ball', and that was true. But what a fast ball! It came up to the plate like a pea shot out of a cannon."

No doubt referring to the 3-0 game between the schools on April 1, The Fullerton Tribune called this the "second of a series of games to be played for the championship of Orange County," while the Santa Ana Evening Blade guessed that "probably another game will be played later to play off the tie, although Santa Ana won the first game of the series." As it happened, Santa Ana would continue their march toward the Southern California championship, but Fullerton's season -- and Walter Johnson's brief high school career -- were over.

The day after the Fullerton-Santa Ana battle, Johnson was in action for Olinda, playing centerfield this time in a 7-6 victory over Tufts-Lyon of L.A. A month passed before his next game of record, a 9-7 loss to the same team in which he played first base. Art Crips (who tried out with the Chicago White Sox, but never made it to the big leagues) was still the Oil Wells' front-line pitcher, as he had been for several years. But two weeks later, on May 28, Johnson made his best professional showing yet, only to lose once more, 4-2, to the Hoegees. Olinda errors allowed all four runs in the first two innings, after which Walter was invincible. He finished with 12 strikeouts while giving up just six hits, two walks, and three hit batters. The Hoegees, "...failing to find them with the bat, turned their anatomy toward the ball, getting it amidships," reported the Anaheim Gazette.

Another game at first base, a 6-6 tie with the L.A. Hamburgers, was followed on June 11 by -- finally -- a Johnson victory in his ninth recorded pitching appearance (three with the high school). With good support from his teammates this time, he beat the Hoegees, 9-4, on a 5-hitter, with seven strikeouts. The Gazette followed its game report with the intriguing note that "Kid Johnson is going to have a tryout in the box with a Los Angeles team at Chutes Park this week." There isn't another reference to this, so whether it took place, or with whom, is a matter of conjecture. Chutes Park, later known as Washington Park, was home to the Los Angeles team of the P.C.L., variously referred to in the local press as the "Looloos", "Seraphs" or "Angels". Although the Looloos were in town at the time, Chutes was also used by semipro clubs when the P.C.L. team was on the road. The moniker "Kid Johnson" had now been picked up by the Fullerton Tribune also, making it Walter's first "official" nickname. A 13-9 loss to Tufts-Lyon on June 25 included a bad outing by both Crips, who gave up nine runs on eight hits in the first three innings, and Johnson, who allowed the L.A. boys 11 more hits in the last six frames.

His next appearance, however, at Ventura July 9, was his best yet. In a game described by the Ventura Republican as "one of the most sensational games that ever graced a diamond in this part of the state", and remembered by Faye Lewis as "one of the most exciting games ever played by the old Olinda team", Walter matched goose eggs for twelve innings with Ventura's lefthander, Andrade. Finally, Olinda put over two runs in the top of the thirteenth, then hung on as Ventura rallied for one in the home half of the inning. Altogether, he struck out 13 in a 6-hit, no walk, masterpiece. Three of Ventura's hits were classed "lucky" by the Tribune, but one was decidedly not -- a hit by a fellow Johnson, George, the Ventura first baseman, which led to Ventura's only run. Olinda's first baseman, Bob Isbell, described Walter just standing and grinning in admiration, watching the tremendous clout gain momentum. Both Isbell and Lewis recalled George Johnson's hit as a home run, but the box score reveals only a double and triple for George. In any event, Walter retired the next three Ventura batters to preserve a well-deserved victory. But his continuing inconsistency resulted two weeks later in a 10-5 pounding at Rivera in which he blew up for 7 runs in the last two innings. Nine stolen bases against Johnson and his normally reliable catcher, Guy Meats, didn't help, and pointed out his lack of finesse in holding runners on base.

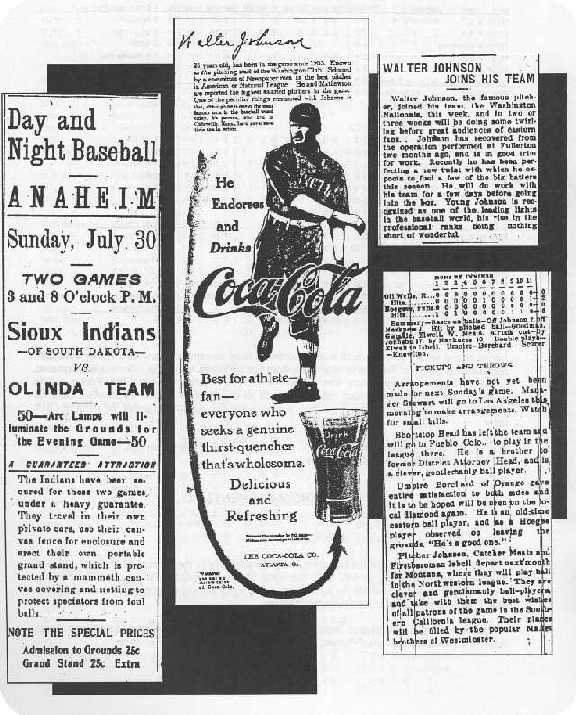

Johnson's first season with Olinda ended on a positive note, a 9-5 win July 30 over -- of all things -- a Sioux Indian team from South Dakota. An advertisement in the Fullerton Tribune hailed them as "a guaranteed attraction...the Indians have been secured for these two games under a heavy guarantee. They travel in their own private cars, use their canvas fence for enclosure and erect their own portable grandstand, which is protected by a mammoth canvas covering and netting to protect spectators from foul balls. Fifty arc lamps will illuminate the grounds for the evening game (of a day-night doubleheader)." The ad saved for last mention of the "special" prices (there was usually no admission), 25 cents general, 50 cents for the grandstand. But this was no deterrent as 1,000 curious spectators jammed into Athletic Park for each game. Johnson struck out ten Sioux in the opener, and they retaliated by hitting the first home run against him. They wreaked true revenge, though, in the night game, scoring 14 runs in the first inning of a 17-5 massacre of the locals.

These colorful contests marked the end of Olinda baseball for a while when it was announced that the Oil Wells were disbanding. For several months, financial problems had plagued the team, and the Anaheim Gazette's importuning of the fans to "loosen their wallets" became a constant refrain accompanying reports of the games. "Baseball is the national game and the ball put up here is the best of amateur playing on the coast," ran their argument in one instance, a game in which only $15 of the $24 needed to make expenses was gathered in the first passing of the hat. Manager Tom Young addressed the large crowd from the middle of the diamond, and his pleadings brought accounts into balance with a second round of contributions. On another occasion Jack Burnett, "the amiable captain, gave a forceful dissertation on the cumulative effect of frenzied finance."

The Oil Wells paid transportation and meals for visiting teams, and after their own expenses there was often little left for the players. This didn't bother Johnson: "My share was often 50 or 75 cents, and frequently nothing," he wrote a few years later. "This, however, did not worry me as the keen enjoyment of the game was compensation enough." Walter was 17 and living at home, but the older men, some of them promised a regular salary, weren't so philosophical. By late June, Tom Young had had enough and turned over the managerial reins to Walter Woodruff, the team's scorer. Anson Mott and Clair Head, third baseman and shortstop, had already left for minor league ball in the east. With the breakup of the team, Jack Burnett was off to L.A. for a tryout with the Looloos. Rivera had expressed interest in Walter two weeks before, when rumors of the Oil Wells' imminent demise had first begun to circulate. Now, In spite of touching him up for 10 runs a week ago, they didn't hesitate to grab him for their team.

There were no team standings kept for the circuit in which Olinda played, and no statistics, official or otherwise. But enough box scores appeared in the papers to present a useful summary of Johnson's initial "season" with the Oil Wells. (Sadly, this can't be said for the high school games). There are 15 games of record -- 9 pitching, 2 at first base, and 4 in the outfield. On the mound he won 3 and lost 5 (all starts), with no decision in his single relief appearance. In the 9 games, he pitched 83 innings and gave up 43 total runs (many of them unearned, presumably) while striking out 79. In the 8 games (75 IP) for which hits were specified, Johnson allowed 59; in the 7 games (66 IP) where walks are listed, he gave up 9; in 12 games for which offense is shown, he was 4 for 47, an .085 BA; and in 12 games of fielding, he had 48 chances with 2 errors, a .958 FA.

It's worthwhile to note that from the very beginning of his pitching career, Walter Johnson demonstrated excellent control. As a semipro pitcher, his average number of walks allowed per nine innings was regularly less than two. This pinpoint control continued throughout his major league career, as he never allowed more than two walks per nine innings until the lively ball era, when he may have felt more of a need to pitch around batters. At no time in Johnson's career did he exhibit the wildness that plagued such other legendary flame-throwing pitchers as Rusie, Feller and Ryan.

Also moving to the Rivera club were Guy Meats and Bob Isbell. Meats was Johnson's favorite receiver, and he followed Walter through five years of semipro battles in California and a summer in Idaho. He loved to catch Johnson, and many years later shared with an interviewer the surprising secret known by all of Walter's catchers:

"He was the easiest man I ever caught," Meats declared. "Despite his great speed he threw a light ball, and his control was so perfect that you always got what you asked for. I could have caught him in a rocking chair, and that was before anyone had come up with the idea of a jointed glove."

Meats went on to talk about Walter's disposition on the mound, no secret at all during his career, in fact an important feature of the Johnson legend:

"If an umpire called a close one, Walter never took issue with him, because he believed that the umpires make mistakes the same as players do and the next one might be in his favor. He just tossed the next one over the plate in such a fashion that it left no doubt in anyone's mind. He never complained or noted an error behind him."

Their first game with Rivera came on August 13 and was a great success, as Johnson struck out a dozen L.A. Leonardts batters in a 12-4 win. Going the distance for Leonardts was "the celebrated league southpaw," 40-year-old Phil Knell, who had pitched in the National League from 1888 to 1895 and whose career in the "outlaw" California League spanned 20 years. According to the Whittier News, Leonardts brought a large group of fans with them from Los Angeles, expecting to avenge a loss to Rivera two weeks before in which, they alleged, all their good players weren't available. The L.A. contingent bragged that they had never lost a game before that one, with Knell apparently mouthing off the most. After Rivera knocked him around for 12 runs (even Johnson had two hits), Knell was "ridiculed mercilessly" by the crowd. Following this game, there was no baseball activity at Los Nietos for almost a month -- except for a contest between the "married men and single men of Rivera." When play resumed Sept 10, however, there were games three Sundays in a row, Johnson splitting two on the mound and playing left field in between. His four-game career with Rivera ended with a record of two wins and a defeat.

As the summer ended, instead of returning to high school Walter enrolled in the Orange County Business College. Nearing his 18th birthday, the age at which most students have graduated, he might have felt too old to be going into the tenth grade. Work in the oil fields, while steady, was also hard and dangerous; the Olinda columns of the Tribune repeatedly mentioned laborers who were "mashed" or "mangled" on the job. A bright young man who was capable of making a good living in a less risky profession would certainly take advantage of any opportunity to do so. Walter accepted a job at the Stern and Goodman grocery and dry goods store near his house on Santa Fe Avenue in Olinda. The proprietor, Maurice Ray, who was the scorer for the Oil Wells' games, apparently encouraged him to continue with his schooling. Walter studied bookkeeping, and it's possible that Joe Burke, working in that capacity for the railroad, was an influence. Walter earned $4 a week at the store, and according to Guy Meats most of that went into the card games always in progress in the back:

"He didn't drink or smoke, but how the son-of-a-gun liked to play poker! Any time there were four or more in a room, Walter would start a poker game and he could draw to anything. He was such a soft touch for any amount. I could have retired on what he gave away."

Late in September the Fullerton Tribune reported an effort among "the Anaheim people" to get the Oil Wells playing again. Tom Young's reaction was, "nothing doing," the paper reported, "unless the team has a more satisfactory guarantee of expenses." But two weeks later came the announcement that Olinda would indeed be in action again on the local diamond. Young had "secured more favorable concessions this year than last," perhaps from the saloons. Whatever the particulars of the deal, it had the practical effect of increasing the kitty for nine players to $20-$25 per game, a reasonable amount considering that a "roustabout" in the oil fields started at $1.50 a day. The team was reorganized, with Anson Mott elected captain, and play resumed October 15 with a 4-3 Johnson win over the Hamburgers.

Walter was slammed for 10 hits a week later in a 7-3 loss to Tufts-Lyon. But in his next start, on November 12 against the same team, he crafted his first semipro shutout -- a 1-hit, 13-strikeout, 1-0 gem. He also went 2 for 3 at the plate, and had the Anaheim Gazette gushing: "The best game of ball ever witnessed here...with Kid Johnson as the star performer...the way he struck them out was wonderful. Johnson is no doubt one of the best amateurs in the state and has the stuff in him to send him up the line." Just how far "up the line" he was to go, they couldn't have imagined in their wildest dreams. But if Walter, 18 years old now, harbored any doubts about his ability to pitch at this level, this game should have shelved them. In any case, It started him on his first winning streak, and it was two months before he lost again.

At first, it looked like the familiar pattern of inconsistency when Johnson followed with a rocky win over Hamburgers, 8-5. But then he fell into a groove of four solid outings in a row, starting November 26 with a 2-hit shutout of the L.A. Examiners and ending on New Year's Eve with a 5-hit blanking of Christopher-Levys, with back-to-back 6-2 wins over Leonardts and Hoegees sandwiched in between. 1906 began inauspiciously with a 4-1 loss at Pomona in which three Olinda errors by the normally sure-handed Mott and Head were responsible for all but one Pomona tally. Johnson came back on January 28 to pitch the Oil Wells to a 14-4 win over Tufts-Lyon as the Anaheim Gazette summed up his performance, "Johnson was there with the goods as usual." He followed that effort on February 11 with a 5-4 squeaker over Rivera, allowing 10 hits but also striking out 11. More significant than the win, however, was the presence of scouts in the stands, one of them the most important baseball man in Southern California -- Frank "Pop" Dillon, manager of Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League (and a first cousin to Clark Griffith). This news was withheld from Walter, however, for fear that it might make him nervous. When he was introduced after the game to Dillon and to Russ Hall, manager of the Seattle P.C.L. team, he had no idea who they were.

Joe Burke: "Walt's pitching got noised abroad

throughout Southern California. The games we were playing Sunday after

Sunday turned the eyes of a number of scouts in our direction. I well

remember one Sunday when Frank Dillon, manager of the L.A. Coast League

team, and Rusty Hall, of the Seattle team, came down to look us over.

One of my pet ambitions at that time was to get Walt into fast company.

I felt sure that if he had half a chance he would develop into something

really great. We all liked him. He was our kind of fellow. So when we

heard that Dillon and Hall had their eagle eye on us we gave the lad the

best support there was in us. After the game I led a delegation of Oil

Wells players to where Dillon had been sitting in the little grandstand

directly back of the catcher.

'What did you think of the kid?', I asked Dillon.

'Well,' said Dillon, 'he won't do yet. He telegraphs

everything he throws.'"

His style of bringing the ball back in full view before he whipped forward with the pitch was apparently enough to convince the ex-major leaguer (1899-1904) Dillon of Johnson's unsuitability for the higher leagues. He would hear that objection to his delivery many times -- and would never change it. Dillon's other criticisms, of Johnson's trouble holding runners, and being too "green", were more valid. But if this rejection didn't hurt enough, Hall hadn't paid Walter any attention at all. He had been sitting on the ground off third base during the game, watching Anson Mott and Jack Burnett. After the game Hall signed them both for his Seattle club, and Joe Burke sadly delivered the news to Walter of the lack of interest in him.

Perhaps determined to prove them wrong, the next week he struck out 15 Downey batters, his highest total yet, in a 16-1 romp. After shutting out Rivera 6-0 on February 25, he came back the following week with a lackluster 5-3 loss to the same team in which he gave up 11 hits. This off day couldn't have come at a worse time, as Russ Hall, along with another scout, was again on hand looking for more talent. The Anaheim Gazette reported of Hall that "he is quoted as saying that Kid Johnson is a comer," but this must have sounded hollow when again no offer was forthcoming. Art Crips made his first appearances with the team since November, pitching two of three games remaining on the schedule. Johnson ended the season in style on April Fool's Day, however, with a sparkling 7-0, 11-strikeout, 5-hitter over Hamburgers.

Johnson's growth as a pitcher in his second season with the Oil Wells is clear in the numbers. His 12-3 won-lost record in 15 appearances of record, all complete games, includes 5 shutouts. In 134 innings he gave up 37 total runs, or 2.5 per nine innings (compared with 4.7 his first Olinda season), with an average of 9.8 strikeouts (8.6 a year ago). Hitting improved slightly (a .143 average). But his obvious improvement was small consolation as he watched many of his teammates moving up to the minor leagues. Burnett and Mott left in mid-March for Santa Barbara, where Seattle trained. "Duke" LeBrandt ("the best catcher the Oil Wells ever had," according to the Gazette), who had temporarily moved Guy Meats out of his job, was picked up by Butte, Montana. But a week after the Olinda season ended, and it seemed there was no baseball to look forward to for a while, Johnson's situation changed dramatically. Jack Burnett had been traded from Seattle to Tacoma (Northwestern League), and had apparently told his new club about the hard-throwing kid he had been playing with in California. Now, to Walter's great surprise, a telegram arrived from Tacoma with an offer of a position on that team.

Amazingly, Johnson did not jump immediately at the chance to move up to the minors. Instead, in an early example of the caution that preceded decisions throughout his life, and with apparently no concern that he might never get another chance like this one, Walter left the matter entirely up to his parents. "Johnson has not decided yet whether he will enter the league this year or wait until next season," reported the Fullerton Tribune. But neither Minnie nor Frank Johnson objected to Walter's trying his fortunes in Tacoma. He had always been responsible and shown good judgment -- "a model boy, as good as they make them," Minnie, not one to exaggerate, described him. And Frank, the great baseball fan, must have been thrilled at the prospect. Others, though, relatives and neighbors, were horrified, and hurried to warn his parents of what would become of Walter if he turned to baseball as a profession. He wired his acceptance to Tacoma.

At Minnie's insistence that he be well dressed for his new job, Walter paid $12, which to him "seemed like the earnings of a lifetime," for a new suit. Boarding the train at Fullerton, the suit under one arm and a cheap leather satchel full of Minnie's sandwiches in the other, he was off for the great northwest. (For the story of Johnson's adventures in the Wild West, see "The Weiser Wonder: Walter Johnson in Idaho", immediately following this article).

1 One of the two Rivera pitchers that day was a semipro star named Walter Settle. This may not have been Walter Johnson's only encounter with Walter Settle. The following article from the 60th anniversary edition of the Norwalk Call, printed 19 Oct 1952, was sent to me by Settle's granddaughter, E Dee Merriken:

Walter Settle had developed into a promising baseball player, and in the teams that were made up in the Norwalk area he used a good pitching arm to good advantage. Los Nietos, an all Mexican team, put up a powerful contest on the 4th of July in '96, in a lot across the street from the "Call", but was mowed down by Settle's superior pitching. Later, Settle developed into a ball player who was in great demand, but even big league ball was a tramp existence in those early days. Settle did play for Ned Hanlon, an early Brooklyn player who was wintering in Los Angeles, and he pitched a scratch team to many victories. When Settle pitched for Whittier, he went up against young Walter Johnson, who was pitching for Santa Ana before his name became legendary in the baseball world. Settle won in a thrilling 13-inning game, two to one...

During Johnson's triumphant return to Southern California after the 1924 World Series, the Fullerton News' 27 Oct issue ran an interview with the Big Train's former teammate, Faye Lewis. Among many other reminiscences was a mention of possibly another Johnson vs. Settle pitching matchup:

Another pitching duel engaged in by Walter Johnson was against the Downey team, led by the famous speed ball pitcher, Walter Settle of Norwalk. This resulted in a win for Settle over Johnson by a score of one to nothing...

I can find no trace in my research notes of either of these games. Is one or the other the same as the Olinda vs. Rivera game on 29 Jan 1905 which was reported in the Whittier News? Maybe not! E Dee tells us "My Grandfather told both David Settle (Settle's son) and Frank Rainier (Settle's nephew) that he had pitched three games against Walter Johnson." It sounds like there are still two Johnson vs. Settle games missing from our Johnson chronicle.

I was unable to locate any surviving newspapers from the Norwalk or Downey area while searching for stories of games in which Johnson might have appeared during the 1904-1910 period. There are a number of dates during this time for which I could find no report of a game. It isn't at all unlikely that there were additional games for which Hank Thomas and I were unable to locate any information. We thank E Dee for sending this tantalizing bit of information and welcome any additional information which readers may wish to contribute to our still unfinished Johnson research project.

-- Chuck Carey, Feb 2002.

After writing the footnote above, I received e-mail from none other than Walter Settle's son, Dave Settle, who informed me:

From very young until I joined the Navy at almost 18, my Dad and I talked baseball. We played catch regularly until he was at least 78. He loved Walter Johnson. Although, athletically speaking, almost from an earlier generation, being born 9/1/76, he was extremely proud to have known Johnson.

Yes, there most certainly were three games between the two. My Dad won 2-1 and 1-0, and lost 1-0. He claimed that "I always had the better team behind me" but there wasn't the slightest doubt in his mind about who was the better pitcher.

I do remember one more thing. My Dad, an excellent hitter who typically batted 6th or 7th, got a hit off of Johnson, a single that "accidentally hit my bat"...

In 2004, E Dee Merriken published her novel, Dream Season, which I obtained from amazon.com. The main character in this book is Walter Settle. Walter Johnson is a minor character who appears toward the end of the story. Although E Dee mixes fact and fiction in her account, the story rings true. I highly recommend the book to anybody who is interested in getting the feel of the "early days" of southern California and of its lively semi-pro baseball scene. E Dee was kind enough to give me credit for providing some of the background information she used in writing Walter Settle's story.

| Previous | Intro | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Epilogue | Stats | Next |

| Idaho article |