Shortly after Johnson's return from the big leagues, the "California Winter League" was organized. The 12-team circuit had Pasadena, Hoegees, and Morans from last year's Southern California League, with new teams from Santa Ana, San Pedro, Santa Barbara, Santa Monica, Dolgeville, and four clubs from Los Angeles. Anaheim and San Bernardino were rejected due to inadequate fields and small rosters, and it was boasted that "all teams are made up of players from the Eastern and Coast leagues." This greatly overstated the case, as the rosters were still made up mostly from local talent, but there were many professional players and some present and future big-leaguers of note: Elmer Flick, Gavvy Cravath, Fred Snodgrass, and of course, Walter Johnson.

Johnson joined up with the Santa Ana team, called the "Stars", at a salary of $5 a game. Santa Ana was 15 miles due south of Olinda, about twice as far as Anaheim and on the same spur of the Southern Pacific Railroad. In the fall of 1906, a local sporting goods merchant and baseball fan A. E. Hawley had built a ballpark on farm land he owned just west of the city. (Hawley Park was at Ninth and Bristol streets.) He organized a team and appointed Ed Crolic, a local billiard parlor owner, manager.

The winter season started for Johnson with a non-league doubleheader on October 27. He played centerfield against Huntington Beach in the first game, hitting a home run -- his first ever -- to win a five-dollar prize which Hawley had offered to any batter hitting one out of his park, and making a throw the locals talked about for years. Lester Slaback, long-time Orange County court reporter, was in left field for the Stars, and 50 years later told Eddie West of the Santa Ana Register what he saw:

"The other team had a man on third base with one out," Slaback recounted. "The batter hit a line single to center. The ball hit in front of Johnson and he fielded it on the first hop. Walter threw the ball to the plate like a shot out of a gun. Guy Meats was catching and Johnson's peg bulleted into his glove, ankle high, just in time to nail the baserunner. That's the only time I ever have seen a man thrown out at home [from third] on what was a clean base hit. Walter's throwing ability was unbelievable."

Johnson's pitching in the second game wasn't bad, either, as he three-hit the Hoegees, with no walks and 11 strikeouts, in a 1-1 tie called after nine innings for darkness. Two months in the major leagues had taken the rough edges off Walter's game, as Bob Isbell recalled:

"What a change a few months in the big leagues made in his throw to the bases! When he played with us as a kid, he made a few false motions before he got the ball to a base. But when he returned at the end of the season, he got his throws there faster and straighter than anyone before or since. It was suicide to try to steal a base on him."

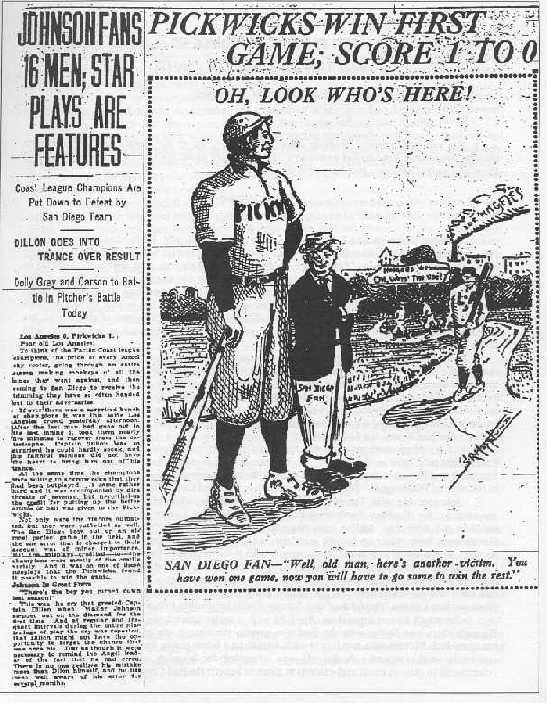

The California Winter League wouldn't start for two more weeks, so Johnson agreed to join the San Diego Pickwicks for a series of games against the P.C.L. champion Los Angeles Angels. The Pickwicks had won the semipro Southern State League, and the five-game set was being billed as for the "Coast Championship." Walter arrived in San Diego on Saturday, November 2, in time to have his picture taken with the Pickwicks in their new uniforms. He watched as they beat the Dyas and Cline club in the first of two warmups for the coming series. The victory was a good omen, Jack "Big Chief" Meyers, the Pickwicks superstitious catcher, told the San Diego Union: "First time I ever knew it to happen. Never played on a team before that was able to win the game after having its picture taken." But the jinx had only been postponed, as Johnson lost his last game as a teenager the next day, 4-2, five Pickwicks errors contributing to the defeat.

The Los Angeles Angels, rated by the Union "one of the strongest teams that has ever been on the west coast", had a lineup almost entirely of past or future major leaguers. "Dolly" Gray (Wash A.L. '09-11) was the best pitcher in the P.C.L., with Bill Burns (A.L. '08-12) and "Judge" Nagle (Pitt N.L. '11) filling out the staff. "Pop" Dillon, manager and first baseman, was a five-year major league veteran, and both Curt Bernard at second and Kitty Brashear at third had had cups of coffee in the National League. Rube Ellis (St.L A.L. '09-12) patrolled centerfield, with "Rosy" Carlisle (Bost A.L. '08) in left. Ted Easterly (M.L. '09-15) was the Angels' catcher. "Gavvy" Cravath, their rightfielder and future 6-time National League home run leader, had been sold to the Boston Red Sox and wouldn't play in the series.

The Pickwicks, though clearly not in the same class as the Angels, didn't lack for luminaries of their own. Meyers was behind the plate, and second baseman Tom Downey would play six years in the National League. Pitcher Alex "Soldier" Carson would make it to the Chicago Cubs ('10), and Bergeman had been on the Angels' staff. They also had Walter Johnson, who "is so well known he requires but little mention", the Union declared. "Six months ago he was an unknown corner-lot twirler in Anaheim. There is not a sporting writer who has seen him work who does not predict that in another year he will be the best in the business."

On November 7, the day after Johnson's 20th birthday, the "championship" series began at San Diego's Palmer Park, at 25th and Newton Streets, at what is now the San Diego end of the Coronado Bay Bridge. He celebrated by shutting Los Angeles down on three hits in outdueling Bill Burns, 1-0. 16 Angels went down on strikes and Walter issued just a single pass. Only two men got as far as second base. His battery-mate Meyers was the other star, banging out three of the five Pickwicks hits and cutting down two out of three trying to steal. "Dillon Goes Into Trance Over Result," gloated the Union:

"If ever there was a surprised bunch of champions, it was this Los Angeles crowd yesterday afternoon. After the last man had gone out in the last inning, it took them nearly five minutes to recover from the catastrophe. Captain Dillon was so surprised he could hardly speak, and his faithful minions did not have the heart to bring him out of the trance. 'There's the boy you turned down last season!' This was the cry that greeted Dillon when Walter Johnson stepped out on the diamond for the first time. And at regular and frequent intervals during the entire nine innings of play the cry was repeated, that Dillon might not have the opportunity to forget the chance that was once his. There is no one who realizes his mistake more than Dillon himself, and he has been well aware of his error for several months. But the crowd delighted in rubbing it in, and it galled him to stand on the coaching line near first base and watch man after man, including the heaviest hitters on the nine, step to the pan, nearly wrench their vertebrae out of joint in wild and ineffectual attempts to connect with the leather as propelled by the good right arm of Johnson, and then retire with more or less bad grace to the bench."

The Pickwicks had only one Walter Johnson, though, and Los Angeles overwhelmed Carson and Bergeman the next two days to lead the series, two-games-to-one. San Diego fell apart completely behind their regular pitchers, committing five errors in the first game and an egregious ten in the second. To make matters worse, Meyers suffered a badly cut finger in the second game and was out of action for the rest of the series. Duke LeBrandt, the former Olinda catcher, took over for him behind the plate. A Sunday doubleheader on November 10 would decide the championship.

The morning game was a thriller, a 4-3 Pickwicks win to even the series. Johnson relieved Karns, the San Diego starter, in the sixth inning after he injured his hand fielding a ground ball. Karns had given up a pair of runs to bring the score to 4-3, leaving Walter with the bases loaded and one out. A bunt attempt was turned into an inning-ending double play, however, and Johnson sailed through the last three frames, giving up one hit while striking out three Angels.

A huge crowd, the largest ever at Palmer Park, filled the grandstand and overflowed all around the field for the decisive afternoon game. A sparkling pitcher's duel between Walter Johnson and Dolly Gray was anticipated, but unfortunately for the Pickwicks and Johnson, it wasn't to be. Walter was in form the first three innings, giving up only two hits. One of those -- a triple in the first by Rosy Carlisle -- brought in a Los Angeles run when LeBrandt allowed a passed ball. In the fourth inning, disaster struck with two outs as a pair of doubles and singles brought in two more Angels runs. As bad as this was for the Pickwicks, with Gray going at top speed for Los Angeles, it seemed even more serious for Johnson, whose arm had gone lame, forcing him to barely lob the ball over the plate. He struggled gamely through the seventh inning, when the Angels pounded out three more runs, before calling it quits. He had given up seven runs on 11 hits, with just five strikeouts, and the series was lost. Pitching a third game in four days had given Walter his first sore arm, and the trip back to Olinda must have been a sad and worrisome one, indeed.

But whatever the nature of Johnson's arm trouble in San Diego, it healed quickly and he was back on the slab for Santa Ana a week later in the Winter League opener. The Santa Ana Register might have been alluding to a continuing problem in the 4-4 tie with the Hoegees -- "Although Johnson was not in his finest form yesterday..." -- but it wasn't apparent in the box score. He fanned 15, gave up three hits and no walks, and only one of the Hoegee runs was earned, the Stars committing six errors behind him. In fact, Johnson didn't have a bad performance in ten games over the remainder of the season. His only losses were by 1-0 to a Santa Barbara team which included his old nemesis, George Johnson, and by 2-1 to the McCormicks, with both runs being unearned. In five games he struck out 15 or more, with a high of 22 in a 12-inning 0-0 tie with San Pedro on January 5. In his last game, against the Hoegees two weeks later, he fanned only nine but had a no-hit, no-walk game in which the only runners reached base on errors.

Johnson's season in the California Winter League was most impressive -- if expected now, considering his stature as one of the bright prospects of the major leagues. In 102 innings, he gave up only 12 runs (1.06 per 9-inning game), averaging 2.9 hits, 0.4 walks, and 13.4 strikeouts a game. The most dramatic improvement in Johnson's game, however, was in hitting. Often appearing in the cleanup slot of Santa Ana's batting order, he batted a lusty .395 in 43 at-bats, with two home runs and five doubles. In a letter to a friend in Washington, he boasted about it: "You ought to see me bat," Walter wrote. "I don't pull away like I used to back there. I hit two over the fence for home runs so far." (Although he became one of the best hitting pitchers ever, it wasn't until his fifth big-league season that his average topped .200.) In the same letter, Walter noted that his arm was "in fine shape."

But if Johnson's arm was sound, another medical problem appeared in the early weeks of 1908. He missed his scheduled start on January 12, and in its account of his no-hitter a week later the Register described him as "not in the best of shape," reporting that he had been sick for the past week and a half. For the next month, George Coleman (Santa Ana High) and George Cody took over the pitching, with no word about Johnson until the Santa Ana Evening Blade noted of a February 23 game that "sickness prevented Johnson from pitching." Suddenly, on the 27th, came word that Walter was in the hospital in Fullerton undergoing an operation.

In bed for the past two weeks (and having suffered through most of the winter) with an abcess of the mastoid process behind his ear, Johnson had put off surgery, hoping it would heal and allow him to make the Nationals spring training. Seeing his condition becoming critical, though, the doctors ruled that the abcess had to be removed. The Los Angeles Times reported that Walter could be in the hospital for as long as a month, followed by another month of recuperation at home:

"Johnson's relatives are in constant attendance and are doing all in their power to permit the bed-ridden patient to pass the time as agreeably as possible," the paper informed its readers. "Johnson is not allowed to talk much, as the working of the jaw affects his sore ear. He is in considerable pain at times, but the administration of opiates to the wound relieves him. The pitcher is keenly disappointed over his illness as he had expected to work for a record this season. He expressed keen interest in the arrival of the White Sox in Los Angeles this morning, and says he would like to get to the city and see them play, but of course that is impossible."

In fact, Walter's relatives despaired for his life at first, his grandfather, John L. Perry, wrote not long afterward. He was placed on the hospital's critical list following the operation, in which a piece of bone behind his ear was removed with the abcess. Just how much danger Johnson was actually in isn't clear, but the operation and hospital stay did cost him $700 of the $1,100 he had saved from his first season with Washington (almost his entire pay). His recovery from the surgery was painfully slow and was complicated by several relapses (from leaving the hospital too soon). On April 22, the Fullerton Tribune was able to report that "Johnson is improving steadily, but the wound behind the ear, where he was operated on for an abcess, needs time to heal. He goes to the hospital at Fullerton twice a week to have the wound dressed. Johnson, in the best condition weighs 185 pounds, he now weighs ten pounds below that figure. He is up and about his home at Olinda every day, taking light exercise and tosses the ball in light practice with the schoolboys in his neighborhood. But he is cautioned by his physician and family not to overdo himself."

By the last week of May, Johnson's light workouts had progressed to the point where he felt strong enough to test his strength on the playing field. Captained by Walter's former teammate, Bob Isbell, and with Walter's uncle Ray Perry (who was two years his junior) at shortstop, the Olinda Oil Wells had just graded a new ball field near the Olinda butcher shop and were beginning yet another campaign against local amateur and semipro teams. In their first game, on May 24, the Oil Wells took on a pickup team which included Walter on the mound and another Perry, perhaps his uncle Roy, behind the plate. The Oil Wells prevailed by a 5-4 score in the contest, with the only aspect of Johnson's performance of interest to the Tribune being his three strikeouts, followed by a home run, as a batter. A week later, Walter made his farewell appearance with his old team, appearing in right field in a 10-9 Olinda win over Buena Park. Another home run proved that his batting eye had lost nothing during the long layoff.

On June 2, Walter Johnson left Olinda to meet the Nationals in Chicago, his illness having cost him the opportunity for his first full season in the majors. Still underweight and tiring easily, Walter took another two months to get into form. Once in condition, though, he performed pitching feats (three shutouts in four days, five complete-game wins in eight) that electrified the baseball world.

| Previous | Intro | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Epilogue | Stats | Next |

| Idaho article |