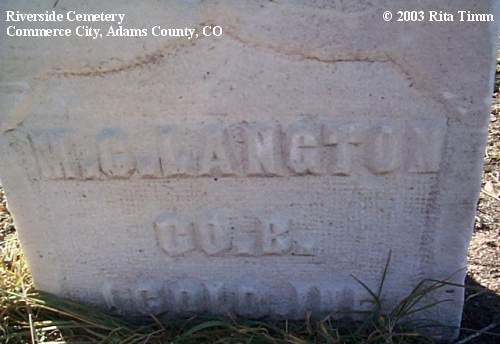

Mack Langton's grave. Mack is listed as M. G. Langton in the Riverside photo page.

At Find A Grave, his middle initial is given, correctly, as C.

Although we know little about the very short life of Jeanette's grandfather, and all those who might remember him are long gone, we learned enough while researching his service in the Spanish-American war that we thought it would be worthwhile to put together a page for him. Mack Langton happened to participate in events which had a great influence on American history, although it is likely that, as a Private in the infantry, he wasn't aware of the "big picture" and the intrigues and machinations that were going on at higher levels which affected him and his buddies.

McConnell C. Langton was born in Seward, Nebraska, 31 Jul 1875, the son of James Caldwell and Elizabeth K. (Sterrett) Langton. Shortly after his birth, but before his brother Frank and sister Fannie were born in 1879, he and his family returned to their earlier home in Moultrie county, Illinois, where they were counted in the 1880 census. Mack's namesake, his uncle McConnell Langton, was living with the family at that time.

Some time during Mack's boyhood, his family moved to Denver, Colorado, where he was listed in the 1892 city directory as a carrier for a local newspaper, the Denver Republican.

What came to be known as "a splendid little war" began when Congress declared war on Spain 25 Apr 1898, after several years of tension between the two nations and the 15 February explosion of USS Maine in the harbor at Habana, Cuba. In the United States, President McKinley appealed for volunteers to serve in the war against Spain. Mack Langton mustered in to Federal service along with Company B of the 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry 1 May 1898. (The Colorado State Archives Military Records list him as Langton, Mark C.)

On that same day, halfway around the world, Commodore George Dewey's Asiatic Squadron destroyed the Spanish Pacific Squadron in the Battle of Manila Bay. Dewey couldn't follow up on his victory because he didn't have enough troops to occupy any Philippine territory beyond the Cavite naval base. The Spanish Army was still intact, although under attack by Filipino rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo, who declared the Philippines' independence from Spain 12 Jun 1898.

All over the United States, patriotic celebrations took place as volunteer units marched off to war. The First Colorado, commanded by Col. Irving Hale, paraded through Denver on 17 May. The following day, "U.S. President McKinley ordered a military expedition, headed by Major General Wesley Merritt, to complete the elimination of Spanish forces in the Philippines, to occupy the islands, and to provide security and order to the inhabitants."1 More than 10,000 troops were assembled for the assault, among them the soldiers of the 1st Colorado. The various units under Gen. Merritt's command were designated the U.S. Eighth Army Corps.

An undated clipping describing Company B's departure from Denver is available at the Arapahoe County2 COGenWeb Project site. Although the transcriber guessed that the clipping was from "Aug/Sept 1898", it's more likely to be from May or June. The Colorado volunteers embarked from San Francisco 15 June, a part of the Second Philippine Expeditionary Force, more than 3,500 men under Brigadier General Francis Greene, and were distributed among at least two chartered transport vessels -- Arizona and China.

The convoy stopped at Honolulu 25 June (Hawaii wasn't annexed by the U. S. until the following month) and at Wake Island 4 July, where General Greene went ashore to raise the flag and declare the uninhabited island a possession of the United States. They arrived off Manila 16 Jul 1898. Having steamed through the same tropical waters in Summer in a relatively modern naval vessel, I can imagine the state of readiness of these soldiers when they arrived in Manila Bay after 31 days underway in a cramped, poorly-ventilated troop transport. The story of the American troops' arrival and of their initial encampment on Philippine soil, referred to as "Camp Tambo", is told in this 20 July dispatch which appeared very belatedly in the 15 August Los Angeles Times:

... Tambo is fast becoming a military camp of importance. It contained 3000 men today, and the number will be increased to 4500 within forty-eight hours. The First Colorado Regiment, which established itself yesterday, was followed today by the First Nebraska, Tenth Pennsylvania and a battalion of the Eighteenth United States Infantry, and the Utah Light Battery will follow tomorrow...

The entire camp is picturesque. The land is quite the highest between Cavite and Malate, and is well wooded. Mangoes and bamboos line and shade the way. The scene is not so tropical as might be imagined, and the presence of hundreds of natives in multi-colored gowns and costumes goes more to make it so than the foliage.

The men are quartered in individual tents laid out in regular order, and in many instances roofed stands giving additional shade have been erected. The weather has favored the establishment of the camp, for while it has been very hot, there has been little rain. As in the case of the California troops, the Colorado and Nebraska troops had to wade ashore. The launches and canoes which brought them from transports off Cavite were unable to approach very close to shore, and the men had no alternative. Some went to the trouble of stripping, but the majority simply struck out, clothes and all. They were all glad to land, as four days of inactivity on the transports had made them anxious to learn again the blessings of freedom...

We found a lot of information on the First Colorado's rôle in the ensuing action at the excellent Home of Heroes web site. We're quoting only a very small part of their material below. There's a lot more on the Spanish-American war and other episodes in American military history which you'll see when you visit the site. Its webmasters are based in Pueblo, Colorado, and encourage visitors to download and print information from the site.

While awaiting the arrival of General Merritt's Eighth Army, the greatest problem Admiral Dewey faced was in keeping Aguinaldo and his insurgent forces from taking control of Manila. Though the insurgents saw the Americans as allies in their dream of Philippine Independence, political factions were at work to thwart them. Admiral Dewey referred to them as "the Indians" and promised Washington, D.C. that he would "enter the city and keep the Indians out." In its imperial wisdom, the United States began to see itself more and more as a force bent on protecting the Philippine people from themselves, than as a liberating force...

In truth, the 15,000 Spanish soldiers now trapped inside Manila were almost as eager for the arrival of American ground forces as was Admiral Dewey.They knew the American forces to be civilized, even generous to their enemies. After the Battle of Manila Bay Commodore Dewey had wired President McKinley to announce, "I am assisting in protecting the Spanish sick and wounded. Two hundred and fifty sick and wounded are in hospital within our lines." For centuries the Spanish had ruled the Philippines with a heavy--often deadly--hand. They considered the Filipino people to be ruthless, uncivilized, and sub-human. There was great fear that if the city fell to Aguinaldo and his insurgent forces, there would be hell to pay...

On July 17th General Green arrived with the Second Philippine Expeditionary Force of Merritt's Eighth Army, deploying his 3,500 soldiers near a peanut field just south of Manila at a site named Camp Dewey. His position was within range of the Spanish guns, but the enemy withheld its fire, fearing that any offensive action would bring swift and devastating return fire from Admiral Dewey's ships, just off shore.

General Merritt arrived on July 25th, just ahead of the MacArthur's Third Expeditionary Force which had been delayed in transit by rough weather. He promptly took command of the ground war, planning with Admiral Dewey for the fall of Manila. Neither gave recognition to Aguinaldo, or included him in the military preparations...

Between Manila and General Merritt's three brigades at Camp Dewey sat the seaside guardhouse of Fort San Antonio de Abad, just two miles south of the city. The Spanish trenches stretched eastward towards Blockhouse #4, with the insurgent forces in full command to the east. The arriving American soldiers moved into some of the insurgent positions between Camp Dewey and the Spanish lines in the closing days of July, bringing them directly under the enemy guns. There was only sporadic fire from the Spanish artillery as the newly arrived American forces came ashore to dig trenches and prepare for the coming assault. On the night of July 31st, the American forces could restrain their fire no longer.

The one-and-a-half hour battle that followed pitted the infantry and artillery fire of the two opposing forces against each other in what became the deadliest battle in the Pacific. When the Americans returned fire, their positions were exposed and the Spanish adjusted their fire, resulting in 10 Americans killed and 33 wounded. The following day, Admiral Dewey suggested that the Americans hold their fire in the coming days as General Merritt continued to deploy his forces for a final assault. "(It is) Better to have small losses, night after night, in the trenches, than to run the risk of greater losses by premature attack," he cautioned.

In the days that followed, Merritt's forces continued to land and take up positions. The First Colorado Volunteer Infantry moved their own lines eastward to the Pasay Road approaching Manila from the east. Their work was arduous, fighting swamps, monsoon rains, and intermittent enemy fire. At night the Spanish guns continued to fire on American positions, resulting in 5 more deaths and 10 Americans wounded. On August 7th Admiral Dewey sent a message to General Jaudenes warning that unless he orderd his soldiers to stop firing on American positions, the U.S. Naval commander would turn the big guns of his ships on the city within 48 hours.

General Jaudenes realized that the message from the American Admiral was tantamount to a demand for surrender. He also realized that defiance of Dewey's ultimatum would be suicide for himself and his forces. With Aguinaldo and his Filipino force arrayed to the east, Merritt and his 3 divisions to the south, and the U.S. Naval squadron in the harbor, time had run out for the Spanish empire in the Philippines. What followed was five days of negotiations creating an unusual scenario for surrender. It would pit allies against each other, create a strange alliance between enemies, script one of the strangest battles in military history, and set the stage for a sequel war. It would become known as:

The Mock Battle of Manila

...At 8:45 the nervous young soldiers, about to face their first test of offensive combat actions, noted the movement of Admiral Dewey's ships in the harbor to their left. The large war ships began positioning themselves for the attack. At 9:45 the big guns boomed, and large shells began raining down on the Fort at Malate. There was only sporadic and light return fire, and the young Americans advanced nervously to capture the fort. As they neared its now badly scarred walls, the naval bombardment stopped.

Cautiously approaching, the young soldiers of the 1st Colorado found Fort San Antonio de Abad deserted, save for two dead and one wounded Spaniard. Quickly the Americans took control of the abandoned enemy stronghold, looking off towards the east where at 10:30 General MacArthur's brigade had noted the end of the naval bombardment and begun moving again towards Manila. At 10:35 Captain Alexander M. Brooks of Denver, Colorado raised the Stars and Stripes over the captured fort...

[See a large picture of First Colorado troops, probably including PVT Mack Langton, raising the flag over Fort San Antonio Abad, Malate. This is one of several photos of the men of the First Colorado which can be found at the Naval Historical Center.]

Inside the walled city of Manila, General Jaudenes listened to the sound of the naval gunfire. He wasn't concerned. He had already agreed with Admiral Dewey as to how the scenario would play out. On his desk was a piece of paper, the only printed document related to the unfolding events. It sketched out a series of signal flags that, when seen flying from Admiral Dewey's ship, would indicate that it was time for the Spanish commander to order his men to hoist the while sheet over the city that would signify the final act in the mock battle for Manila.

From August 8th to 12th, the opposing commanders had hammered out the details. First, Jaudenes had requested a 48 hour delay in the threatened bombardment in order to obtain permission from Madrid to surrender the city. Granted the delay by Dewey, Madrid refused to permit the surrender. His fate all but sealed, Jaudenes was still more than willing to surrender but for two important details:

- It would be a disgraceful act for the Spanish commander to give up his city without a fight. Such an act would be received with derision and probably court martial upon his return to his homeland.

- The Spanish were still quite fearful of the consequences if the city fell to Aguinaldo and his band of Filipino insurgents.

Resolution of such matters were carefully crafted through the Belgium consul Edouard André. In its final draft, the carefully choreographed sequence of events called for the initial shelling of the fort at Malate, which would be promptly abandoned by its defenders. As the Americans then began their ground advance, Admiral Dewey would bring his ships before the city and hoist the signal flags demanding surrender. Upon seeing these, General Jaudenes would order the while flag raised, and the Americans would enter. As had been the case in Cuba, the word "surrender" was avoided to be replaced by the term "capitulation".

The capitulation of Manila would transfer control to the invading American forces, which would then secure the city and deny entrance to the insurgent forces under Aguinaldo. The brief, bloodless battle at San Antonio de Abad would save face for the Spanish soldiers and their commander, demonstrating that they had capitulated ONLY after a devastating attack.

It was an unusual strategy by two opposing forces, one which would not only save face for the Spaniards, but would also save lives for BOTH sides.

At 11 o'clock, as the two columns converged on the city, Admiral Dewey hoisted his signal flags to demand the Spanish surrender. Over the following tense minutes, nothing appeared to be happening. General Greene entered the city with some of his troops, riding into the Luneta... the city promenade. There he was confronted with a heavily defended barricade, and a group of Spanish soldiers who, like the insurgents, apparently were not privy to the unfolding script. Both sides faced off in a tense situation that could have turned deadly with one, mistaken pull of a trigger. In the bay, Admiral Dewey watched the minutes tick by without seeing the white flag of surrender.

The periodic sniping from the insurgents at the outskirts made the Spanish wary of an American double-cross, while Admiral Dewey wondered if the Spanish were about to pull some kind of quick trick when the surrender flag failed to rise over the city. Tension was reaching the flashpoint when, at 11:20, Admiral Dewey at last saw the white sheet flying over Manila. Quickly he dispatched word to his ground forces to enter and negotiate the surrender terms. (The Spanish had actually hoisted their surrender flag shortly after the signal from Admiral Dewey. It had blended into the background of the sky from the Dewey's vantage point, masking the response. Only when the wind shifted, had the surrender flag been noticable.)

In the hours that followed, the Spanish and American commanders hammered out the final details of the surrender while the foot soldiers took up defensive positions in the suburbs. The 1st Colorado crossed the Pasig River to occupy the districts around San Sebastián and Sampaloc. Some small skirmishes continued from time to time during the afternoon, often precipitated by attempts from insurgent guerillas to enter the city. In the process, the Second Brigade suffered one additional soldier killed in action, 38 men wounded.

By 5:30 in the evening, the fighting was over and the United States Flag flew over the capital city of the Philippine Islands...

The mock battle for Manila occurred on August 13, 1898... more than 24 hours after the signing of the peace protocol in Washington, D.C. at 4:30 P.M. (5:30 A.M. Manila Time) on August 12th. Because Admiral Dewey had cut the only cable that linked Manila to the outside world, news of the war's end reached neither General Jaudenes nor Admiral Dewey until August 16th...

The fears of both Spanish and American commanders of what might happen if Aguinaldo's troops were allowed to enter Manila were a matter of public knowledge and were mentioned in this excerpt from an 18 Aug Los Angeles Times article describing the "battle" and its aftermath:

... Perfect order prevailed in Manila on the evening of August 13. As the Americans marched in guards were placed around the houses of all foreigners, in order to prevent their being looted. The insurgents were not allowed to take part in the attack upon the city, but were kept in the rear of the Americans. In order to prevent bloodshed, they were forbidden to enter the city after the surrender, unless they were unarmed...

The bogus "battle of Manila" wasn't the end of the First Colorado Volunteers' story. They remained in the Philippines for another year. Negotiations between American and Spanish diplomats dragged on until 10 Dec 1898, when the Treaty of Paris, transferring sovereignty of the Philippines from Spain to the United States, was finally signed. The treaty met strong opposition by "anti-imperialists" in the U. S. Senate and wasn't ratified until 6 Feb 1899. During the six-month period following the Spanish surrender, tensions escalated between the American and Filipino forces. Two days before the Senate's ratification of the Treaty of Paris, the Philippine Republic declared war on the United Stares, after an incident on a bridge near Manila in which three Filipino soldiers were killed by American troops.

What followed was neither "splendid" nor "little", but it was most definitely a war. During what is referred to by American historians as the Philippine Insurrection, and by Filipino historians as the Filipino-American War, more than 4,200 U.S. soldiers, 20,000 Filipino soldiers, and hundreds of thousands of Filipino civilians lost their lives. Among the first casualties in this new conflict was one of Mack Langton's Company B buddies, Private Orton Thomas Weaver of Vernon, CO, who was wounded in action in the first week of February 1899.

Company B was undoubtedly in the midst of a number of actions during the next few months. Orton Weaver's grand-nephew has posted an article from the Army's Freedom newspaper which describes a brief, but bloody, skirmish with the Filipinos which may have been similar to the fighting seen by Mack and Company B, although this firefight involved a different company of the First Colorado. In its limited space for "Battles, engagements, skirmishes, expeditions", Mack C. Langton's service record has the following entries:

The conflict between Filipinos and Americans is described as follows in Halsey's Typhoon, by Bob Drury and Tom Clavin:

Having acquired this sprawling archipelago halfway around the world, America didn't quite know what to do with it, and U. S. occupation forces viciously eradicated more than 200,000 Filipinos in the Orwellian-named Philippine Insurrection. American military commanders directing this operation against the "gugus" tended, in the words of one analyst, "to see the conflict as an extension of the Indian extermination campaigns for which they had been trained."

As the warfare continued, all volunteer units were ordered home (their term of service was limited by law) and were replaced by regular army units. The First Colorado left the Philippines 17 July, arrived in the U.S.A. 16 August, and was mustered out of federal service at Presidio San Francisco 8 September 1899. Captain Frank W. Carroll, the company commander, signed Mack's discharge and military record, describing his service as "honest and faithful".

The story of the First Colorado Volunteers' return home is taken from the page describing the founding of the Veterans of Foreign War. Their commanding officer, Col. Irving Hale, had been promoted to Brigadier General by President McKinley...

When Johnny came marching home after the Spanish American War, he did not receive quite the hero's welcome he expected.

Many Spanish American War veterans were mustered out of the service far from home and left to find their own transportation back. Most arrived home virtually penniless only to discover that their hero status was no help in finding employment. Often the jobs they had given up when they answered the president's call for volunteers had been taken by men who had stayed safely at home.

Treatment of veterans who were sick or wounded was especially shoddy. Even the most severely disabled veterans were denied hospital care or medications. Nor were there any government programs to help returnees rehabilitate themselves so that they could resume their places in society. They were given two months' pay ($31.20 for a private), discharged, and sent home to their families...

The First Colorado Voluntary Infantry Regiment returned to San Francisco, where the regiment was mustered out September 8, 1899. So proud of their soldiers were the people of Denver that they ignored the usual policy of leaving men who had "mustered out" to find their own way home from the mustering-out point. By public subscription of funds, they hired a special train to transport the men home to Denver. On September 14th, the soldiers were greeted by 75,000 citizens of their capital city. After a joyous parade and stirring speeches of appreciation for the job the First had done in the Philippines, General Irving Hale ordered his men to fall out for the last time.

Problems began almost immediately for the former members of the First. Like their eastern counterparts, many discovered that the jobs they had held before the war had been taken by others. And those who were unable to work because of disease or crippling wounds belatedly found they had no prospects of rehabilitation or financial assistance from the federal government. Veterans' employment woes were further increased by the depression that gripped the nation. Not only had their old jobs been taken by others, but new ones were almost nonexistent.

A born leader, Irving Hale was a man of tremendous energy and vision. His enthusiasm and loyalty toward his home state and the men who had served under his command made him a natural selection to lead many civic and organizational projects. After the First was disbanded, Hale kept in contact with his men. He talked to those he met on the streets and visited some of them in their homes. What he encountered touched him deeply. It seemed especially unjust to him that men who had suffered during wartime service were now destined by an uncaring government for further suffering and starvation. Hale helped many veterans from his personal funds. He soon became convinced, however, that the only way to right all the wrongs being imposed upon his returning veterans was to form an association...

General Irving Hale became the first president of the Colorado Society of the Army of the Philippines and organized its first reunion, which took place in Denver in 1900. In 1914, it merged with a similar organization of veterans from the East to form the Veterans of Foreign Wars, an organization which exists to this day.

During the Spanish-American War and its aftermath, many more American servicemen were killed by tropical diseases than by enemy bullets. Thousands of soldiers, sailors and marines perished as a result of contracting yellow fever, tuberculosis, smallpox and malaria. In many cases, they didn't die until long after they returned home. Although his military record says McConnell Langton was not wounded during his service, he did contract malaria in the Philippines, which led to his death3 in Denver, Colorado, 7 Aug 1904 when he was only 29 years old. He is buried in Riverside cemetery.

Mack married Ida Mae Inman 15 Nov 1899 in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Ida Mae was born 8 Apr 1876 in Illinois,4 the daughter of Ben and Lucy Ann (Jennings) Inman. She moved with her parents to Minnesota in 1883, then to Colorado between 1895 and 1897. Their marriage certificate, which was provided by great-grandson Mike Herder, lists Mack as being "of Denver" and Ida Mae as being "of Colorado Springs". The 1900 census found the newlyweds ("Mack M." and "Ida May") living at 1936 W. 32nd Avenue, in Denver, along with Mack's older brother William's family.

We don't know whether Mack Langton received any care at military hospital facilities, or any pension or other compensation, for the illness caused by his service to his country. Nor do we know whether he joined General Hale's new veterans organization. We did locate a record of Ida Mae applying for a widow's pension 31 Aug 1904. It is fitting that Mack's daughter Inez, who never knew him, eventually would become very active in the VFW womens auxiliary, most likely because her husband, Francis Tennis, was also a veteran.

Mack Langton's grave. Mack is listed as M. G. Langton in the Riverside photo page.

At Find A Grave, his middle initial is given, correctly, as C.

Children. Mack and Ida's children were:

After Mack's death, on 4 April 1907, Ida Mae married George Sylvester Gale, with whom she and the children were enumerated on 39th Avenue, in Denver, during the 1910 census. The census taker recorded the three kids as Gales! The 1920 census taker got their names right, although in both censuses Ida's parents' birthplaces are listed incorrectly. We notice that nearly half the people on the census sheet are immigrants from Sweden, Austria and Italy. Merle and Cecil had both started working by this time.

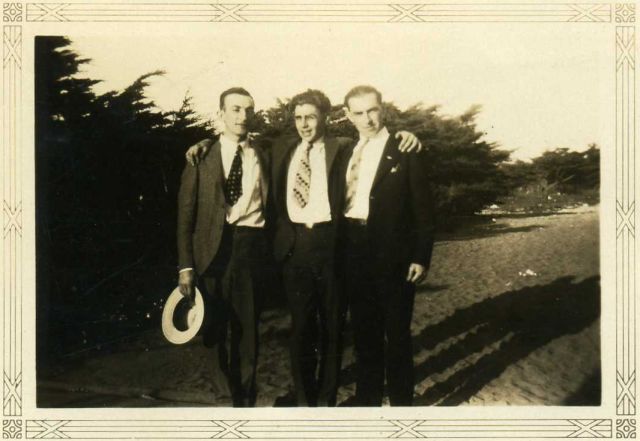

The Langton boys, Merle (l) and Cecil (r), in California some time in the late '20s or early '30s, with their friend Ralph LeFever

One of Mack and Ida Mae's granddaughters, Roberta Gerds, gave us her memories of her grandmother:

Grandma Langton

Ida May Langton, my father's mother, played a very large part in my life when I was little. As far as I know, she didn't have a place of her own, and took turns staying with her three children, Merle, Cecil (Dad) and Inez and their families.

One of my first memories of grandma was when Mom, Dad and I took the train to Colorado when I was 3 years old. She was staying in Denver with Inez at that time. They were living in a second floor apartment and I think we stayed with them. We went to see her mother (my great-grandma Inman) and her sisters, Nora and Theta. We also went to see her second husband, "Mr. Gale". That was the only way she ever referred to him, and I never heard her referred to as Mrs. Gale. My memory of the visit was that we went to a place that seemed to be a big park, with trees and grass. After checking with someone to find out where Mr. Gale was, we walked across a grassy area to a chain-link fence with men walking around on the other side. After a while, an "old man" came over to the fence to talk to us. Actually, I don't remember that he interacted with us much. I think they told me that he was my grandpa, but I don't remember what they said about why he was living in the place we visited. Even in later years when I asked questions about it, I don't remember getting a good answer. I think something was said about it being a home for old men, but I still don't know why he was inside a fenced enclosure.

During my preschool years grandma lived with us and took care of me while Mom worked in the May Company credit office. Sometimes Grandma would take me downtown on the street car to visit Mom. Grandma would dress me up and put my hair in curls and the people Mom worked with would come out to see me, then Mom would come out and we would go downstairs to have lunch in the employee cafeteria. One time Grandma surprised me by taking me to a different place. We rode on several street cars and a bus and she wouldn't tell me where we were going until we got off the bus and waited on the street while a circus parade went by. We followed with the other people to a big lot, and watched them begin setting up the circus. That was the closest I came to seeing a circus, until I was much older, but just seeing the elephants and the performers in the parade was very exciting.

Grandma used to talk a lot about what she would do and what she would buy me when her "ship came in". I didn't know what she meant, so I remember that whenever we went to the beach I would look out over the ocean to see if her ship was coming. I later learned that she was waiting for a bill to be passed so that she could get a pension. I think there was something called the "Townsend Plan". One night I went with her to a meeting about the plan. They had a drawing for door prizes. They stood me on a stool and had me draw names out of a bowl. I must have drawn Grandma's name, because I remember that we won a box of chocolates.

Grandma had long white hair. She brushed it every morning, then wound it up in a bun. I remember waking up in the morning with her sitting on her bed next to mine brushing her hair. She also had beautiful skin and a very pretty face. After I started school, she spent less time with us and more with Uncle Merle and his family.

As Roberta mentions, Grandma Langton "took turns staying with her three children". At the time of the 1930 census, just four days before Cecil's marriage to Bertha, Ida was staying with Cecil in Los Angeles and gave her "marital condition" as WD, widowed. Later, she was living with Inez when Roberta visited her in Colorado. In 1940, the census taker enumerated her with Cecil and Bertha and their two daughters. According to her death certificate, which lists her as Ida Langton, Ida Mae died in Los Angeles 25 June 1943, at Merle's home, 1619 Newby Ave., Rosemead, CA, and had lived in California for 16 years. She is buried in Inglewood Park Cemetery.

The following are some web sites which we found helpful while researching McConnell Langton's participation in the Spanish-American war:

| Last Name | First Name | County | Cemetery | Birthdate | Birthplace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langton | M C | Adams2 | Riverside | d. 7AUG1904 | --- |