An Amish patriarch leaves an intriguing story

and a controversial indenture for his descendants.

The Life of John Melchior Plank, 1767 Immigrant

by Jerold A. Stahly

Many Americans trace their ancestry back to Melchior Plank of Pennsylvania. The traditions about his immigration and his life in America have circulated widely and have been mentioned in many historical and genealogical books as well as in the Mennonite Encyclopedia.

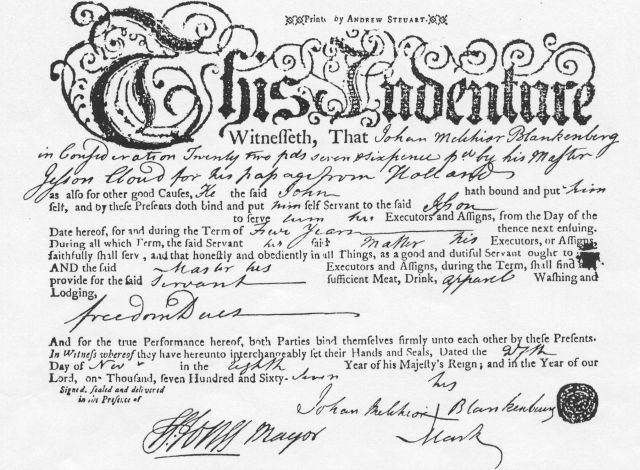

Within the past thirty-five years several descendants have tried to assemble documentary evidence concerning Melchior Plank's life. This has led to some controversy. Harvey C. Plank (1874-1955) of Lagrange, Indiana, possessed a copy of Melchior Plank's will and a 1767 servant's indenture which he claimed belonged to Melchior Plank. The indenture agrees with the tradition in part. However, the indenture names the illiterate servant as "Johan Melchior Blankenberg" with spelling variations of "John" in the text and "Blankenburg" at the bottom. Because of the difference in the surname some researchers have denied that the document belonged to Melchior Plank. In the course of describing what is known of Melchior Plank, this article will offer evidence that he did use the name John and that he was the same person as John Melchior Blankenberg.11

His Origin

Research in America has not revealed the European home of John Melchior Plank. Family traditions assert that he was a Swiss Mennonite, born either in Switzerland or Germany and living in the Netherlands as a refugee.2 Because he was an Amish Mennonite in America and used the surname Plank (Planck, Blank, Blanck), a name known among Amish in Europe, most people assume that he was from an Amish community where this family name was found. If he used the name Blankenberg (Blankenburg, von Blankenburg) in Europe, he may have had a non-Amish origin. Some towns in Canton Bern, Switzerland, and in Germany are named Blankenburg, but this surname has not been found among the Amish. John Melchior Blankenberg may have been an Amish convert as were Nikolaus Stoltzfus and Johann Martin Bornträger, both of whom emigrated from Europe to Pennsylvania in 1766 and 1767, respectively.

Many researchers have searched for evidence of a relationship between John Melchior Plank and other Pennsylvania immigrants. Several Amish Blanck families arrived in 1751-52, settling in Berks and Lancaster counties. Both Dr. Hans Blanck (will probated 1790) of Tulpehocken Township and Hans Blanck (will probated 1794) of Cocalico Township had large families by the time our subject arrived. Efforts to connect him to these families or to other Blankenberg or Delaplank/De la Plank families have all failed.3

Melchior Plank's birth date is unknown. The year 1744, often given in old traditions as his year of immigration, is more likely his year of birth.4

His Immigration

According to Plank family traditions, Melchior Plank and his wife came to America soon after their marriage, but her name was not preserved. Melchior's will names his wife as Margaret. At this time we can only assume that Margaret was the wife who came with Melchior and became the mother of his six children.

Plank traditions variously give the year of immigration for Melchior and his wife as 1744, 1745, or 1765. However, an immigration date of 1744 or 1745 is unlikely for a married couple whose children were born between 1767 and 1783. The name Melchior Plank/Blank cannot be found on ship lists, but "John Melchior Blanckenberg" is listed as a 1767 immigrant.

The Plank family has preserved a popular story about how Melchior and his wife came to America.5 According to this tradition, the couple went to the port in Rotterdam, where they were living, to bid farewell to friends who were leaving for America. The captain told them that the ship would not leave until the next day. He invited the Planks to stay overnight on the ship with their friends, and they agreed. During the night the ship set sail, and the Planks awoke in the morning to find that they had been kidnapped. Upon arrival in Philadelphia they were sold as servants to pay for their passage.

The ship list clearly shows that Johan Melchior Blankenberg left Rotterdam in the summer of 1767 and arrived in Philadelphia in October on the ship Minerva.6 He and the other foreign men signed the required statements of loyalty and renunciation on October 29 at the office of Thomas Willing, the merchant who received the shipment. Being illiterate, Blankenberg placed his mark (X), and someone wrote his name as "John Melchior Blanckenberg." Because his fare had not been paid, he probably returned to the ship to wait for buyers to come, looking for servants. Blankenberg waited until November 27.

This November 27, 1767, indenture for Johan Melchior Blankenberg shows that his passage from Holland was paid by Jason Cloud, Jr., in exchange for five years of servanthood.

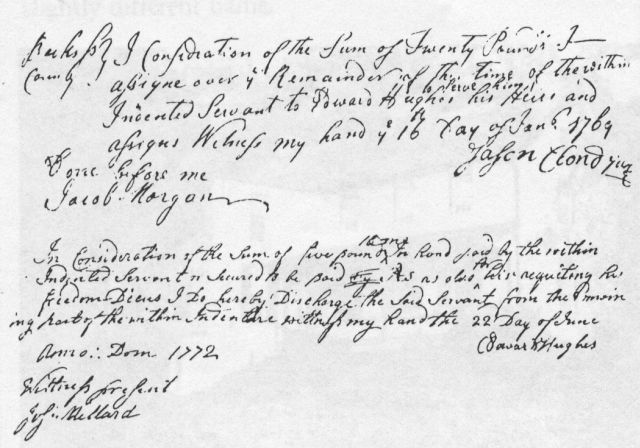

The reverse side of the indenture shows the January 16, 1769, transfer of Blankenberg as an indentured servant from Jason Cloud, Jr., to Edward Hughes and Hughes' June 22, 1772, discharge of him upon payment of £5 about five months prior to the end of his term.

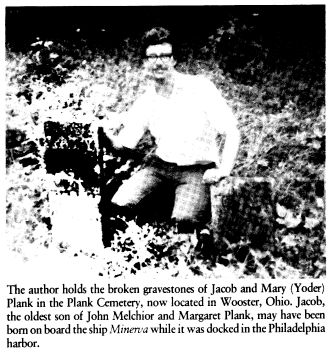

At present we cannot prove that Blankenberg had with him a wife who also was sold to pay for her passage. Having no record of her indenture, we cannot be sure if she was sold along with her husband or on another day to another master. Possibly she gave birth to their first child, Jacob, while waiting on board the Minerva in the Philadelphia harbor. Jacob Plank's cemetery record indicates that he was born on November 6, 1767.7

His Life as a Servant

Family tradition asserts that the Planks were sold to a Mr. Morgan of Berks County who proved to be a severe taskmaster. Sympathetic friends bought the Planks from Morgan and kept them until the debt was paid. This story is supported only in part by the indenture paper handed down in the Plank family. On November 27, 1767, Johan Melchior Blankenberg was bound as a servant for five years to Jason Cloud, Jr., who paid £22 7s. 6d. for his passage. Blankenberg signed the indenture with his mark (+) in the office of Philadelphia Mayor Isaac Jones, who also signed. Jones presumably entered the agreement in his own record book.

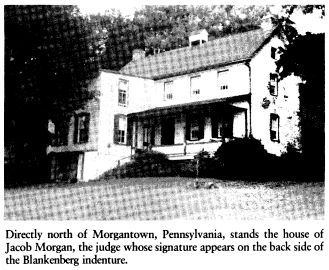

Cloud assigned Blankenberg as a servant to Edward Hughes8 on January 16, 1769, for the remainder of his term. Hughes paid Cloud £20. This transaction was recorded on the back side of the indenture and took place in Berks County in the presence of Justice Jacob Morgan, who must have entered it in his docket book. Cloud and Morgan signed at that time. On June 22, 1772, Hughes discharged Blankenberg on payment of £5 about five months before the term would have ended. Hughes signed along with a witness, Joseph Millard. Whether Millard signed as a justice is not clear.

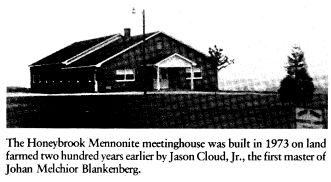

Jason Cloud, Jr. (b. 1732), lived in Honeybrook Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, then still a part of West Nantmeal Township. Although he received a warrant for 150 acres of mountain woodland in 1765, he evidently never paid enough to patent the land and clear title to it. He was probably living on and farming a two hundred-acre tract owned by his father, Jason Cloud of East Caln Township. Both of these tracts were at the northwestern edge of the township, slightly projecting across the county line into Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County.9 Tax records show that 1768 was the only year during which Cloud possessed a servant. A close examination of the 1768 list shows that the assessor first wrote "2 servants" and later amended the entry by changing the two to a one and correcting the amount of tax.10 This may give evidence that Blankenberg's wife was also with Cloud at least for part of 1768. Perhaps she was a free person, or perhaps she had been resold.

Jason Cloud, Jr. (b. 1732), lived in Honeybrook Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, then still a part of West Nantmeal Township. Although he received a warrant for 150 acres of mountain woodland in 1765, he evidently never paid enough to patent the land and clear title to it. He was probably living on and farming a two hundred-acre tract owned by his father, Jason Cloud of East Caln Township. Both of these tracts were at the northwestern edge of the township, slightly projecting across the county line into Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County.9 Tax records show that 1768 was the only year during which Cloud possessed a servant. A close examination of the 1768 list shows that the assessor first wrote "2 servants" and later amended the entry by changing the two to a one and correcting the amount of tax.10 This may give evidence that Blankenberg's wife was also with Cloud at least for part of 1768. Perhaps she was a free person, or perhaps she had been resold.

Jacob Morgan (1716-1792) lived in Caernarvon Township in Berks County, where he founded the town named Morgantown. As a judge he placed his bold signature on the indenture with the words "Berks County." This may have led to the mistaken idea in the Plank family that their ancestor served a Mr. Morgan of Berks County. The story that Morgan was a "severe taskmaster" may possibly apply to Cloud. Records show that Cloud had a problem with debts, which led to his imprisonment at Carlisle in 1773.11

Jacob Morgan (1716-1792) lived in Caernarvon Township in Berks County, where he founded the town named Morgantown. As a judge he placed his bold signature on the indenture with the words "Berks County." This may have led to the mistaken idea in the Plank family that their ancestor served a Mr. Morgan of Berks County. The story that Morgan was a "severe taskmaster" may possibly apply to Cloud. Records show that Cloud had a problem with debts, which led to his imprisonment at Carlisle in 1773.11

Five men named Edward Hughes lived in Lancaster, Berks, and Chester counties during 1769-72. Blankenberg's second master was probably Edward Hughes (1730?-1783?) of Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County, who was more wealthy than his namesakes and lived much closer to Cloud and Morgan.12 This Hughes held over 750 acres of land with many animals and a gristmill, and he was keeper of the Eagle Hotel. Three of his signatures, which are similar to the one on the indenture, have been found.13

Hughes prepared the township assessment list in December 1770. He recorded Negroes and animals owned by residents but not white servants. In the published 1771 list in the Pennsylvania Archives the numbers seem to be the same, but "Servants" is written instead of "Negroes."14 This gives the impression that Hughes himself had no servants that year because he had no Negroes. However, the 1772 and 1773 lists included both types under the designation of "Servants." Hughes had three servants in 1772 and two in 1773 -- evidence that one servant had left his employ.15 That servant was probably John Melchior Blankenberg.

Joseph Millard, Sr. (1709-1781?), lived in Union Township in Berks County and Joseph Millard, Jr. (1743-1817), was taxed there for a while. The father served as a judge in 1768-69, and the son served as a justice of the peace in Chester County after 1795. Often tax lists misspelled their names as "Miller." A "Joseph Miller" appears on the tax lists for Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County as a tenant in 1772 and 1773. Perhaps this was Joseph Millard, Jr., in the course of his various moves. This is a possible explanation of the name of Millard on the indenture.

Family records show that Melchior Plank's son Christian was born in 1771. He was probably born on the land of Edward Hughes in Lancaster County.

Melchior Plank evidently purchased his freedom with money given by friends, whom he may have felt obligated to repay. As the old Conestoga Alms Book shows, the Amish occasionally made church funds available for loans.16 Such mutual aid has always been an important principle for the Amish.

Melchior Plank evidently purchased his freedom with money given by friends, whom he may have felt obligated to repay. As the old Conestoga Alms Book shows, the Amish occasionally made church funds available for loans.16 Such mutual aid has always been an important principle for the Amish.

Pennsylvania law allowed newly freed servants a grace period of six months before they were taxable, and they often remained untaxed even longer. The name of Johan Melchior Blankenberg does not appear in any record after the indenture. Instead, for the new life of freedom he used a slightly different name.

His Life as a Free Man

John Rickenbach (Rickabough, Rückenbacher), an Amish man living in Caernarvon Township in Berks County, signed his last will on May 3, 1774. One item in the will referred to "my House where Melcher Plank now lives in Caernarvon" Township. Rickenbach died before June 28, 1774, when an inventory of the estate was filed. For various reasons the will was not recorded until 1782, and the accounts were not settled until 1784. In 1785 the heir, Jacob Rickenbach, sold the land to John Hertzler, an Amish man, who kept it for ten years.17 Perhaps Melchior Plank stayed on this land as long as he was in the township.

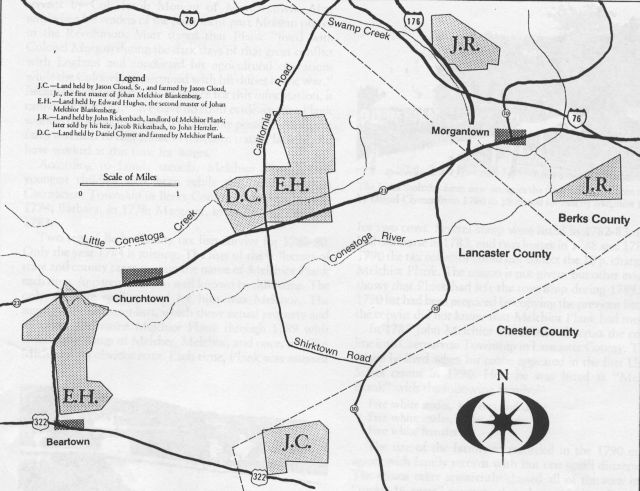

This map shows the geographic location of the tracts of land owned or farmed by the four successive masters and/or landlords of Melchior Plank -- Jason Cloud, Jr.; Edward Hughes, John Rickenbach; and Daniel Clymer.

| Legend of map above: | |

|---|---|

| J. C. | Land held by Jason Cloud, Sr., and farmed by Jason Cloud, Jr., the first master of Johan Melchior Blankenberg. |

| E. H. | Land held by Edward Hughes, the second master of Johan Melchior Blankenberg. |

| J. R. | Land held by John Rickenbach, landlord of Johan Melchior Plank; later sold by his heir, Jakob Rickenbach, to John Hertzler. |

| D. C. | Land held by Daniel Clymer and farmed by Melchior Plank. |

Five tax lists have survived for Caernarvon Township in Berks County for the years 1774-79. The following names appear on these lists:18

| 1774 | Plank, Malikiah |

| 1775 | Plank, John |

| 1778 | Blanck, Melchior |

| 1779 (first list) | Blank, Jno |

| 1779 (second list) | Plank, Melchior |

Careful study of these records show that in each case the one Plank or Blank on the list paid the lowest possible tax for a married man except in the last list, which shows that he paid double the minimum for being a nonassociator, or refusing to join the militia. Therefore, we can be sure that each of these entries is for a resident of the township who owned no land and little else.19

All of these entries must refer to John Melchior Plank. David Morgan, who prepared the first list, either misunderstood the German pronunciation of Melchior or was unfamiliar with the name.20 Aaron Ratew prepared the two lists which named him as "John." Ratew's land lay next to Rickenbach's northern tract so that he probably knew Plank personally.

Melchior Plank paid double taxes as a fine for being a nonassociator during 1779, 1780, and 1781. This gives evidence that he followed the Amish principle of non-resistance by refusing to contribute to the military effort during the Revolution.

In his 1923 article on the Plank family C. Z. Mast presented the tradition about Melchior Plank with some additional details. He stated that Plank was secured as a servant by Col. Jacob Morgan of Morgantown. After reminding his readers of the prominent part Morgan played in the Revolution, Mast stated that Plank "lived with Colonel Morgan during the dark days of that great conflict with England and conducted his agricultural operations while the Colonel was occupied with his duties in the war." Because Mast did not name a source for this information, it cannot be checked.21 We have no solid evidence that Plank worked for Morgan though it is certainly possible. Morgan's farm was next to Rickenbach's northern tract. Plank would have worked at this time for wages.

According to family records, Melchior Plank's four youngest children were born while the family lived in Caernarvon Township in Berks County. John was born in 1774; Barbara, in 1776; Margaret, in 1779; and Peter, in 1783.

Two sets of Berks County tax lists survive for 1780-90. Only the year 1784 is missing. The lists of the collectors of state and county taxes contain the name of Melchior Plank each time. Apparently he was well known by this name. The only alternate spelling used for him was Melchor. The supply tax assessment lists, which show actual property and its value, also name Melchior Plank through 1789 with alternate spellings of Melcher, Melchor, and once, in 1786 Michael -- an obvious error. Each time, Plank was assessed for two cows. Several sheep were listed in 1782-83. Plank had one horse in 1783, and two horses in 1788 and 1789. In 1790 the tax collector could not collect the 10p. charged to Melchior Plank. The reason is not given, but other evidence shows that Plank had left the township during 1789. The 1790 list had been prepared by copying the previous list, and the copyist did not know that Melchior Plank had moved.

In 1789 John Melchior Plank moved across the county line into Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County. This is where he lived when his name appeared in the first United States census in 1790. Here he was listed as "Melchor Blank" with the following family:22

| Free white males, 16 years and older | 1 |

| Free white males, under 16 years | 4 |

| Free white females | 3 |

The size of the family as recorded in the 1790 census agrees with family records with but one small discrepancy. The census taker apparently classed all of the sons in the "under 16 years" category though at the time Jacob and Christian were older.

The tax collectors in Lancaster County again recorded John Melchior Plank with his old name "John." In 1789 "John Blank" was taxed for his two horses and two cattle. "John Blanck" was listed in 1790 and 1791, but from 1792 on, his name was usually spelled as "Melcher Plank" with variations of Melchor and Melker. The 1792 list added a note that Melcher Plank was a farmer living on land of Daniel Climer/Clymer. Clymer lived in Caernarvon Township in Berks County, but he had purchased one tract of land in Lancaster County in 1780. Perhaps Plank farmed this land until he left the township in 1804. Clymer sold the land in 1806.23

In 1800 the United States census recorded a "Michael Blanck" in Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County. This was definitely Melchior Plank; his name appeared on tax lists at the time as a resident of that township. Family members were listed as follows:24

| Males under 10 years | 1 |

| Males 45 years and older | 1 |

| Females 16 to 26 years | 2 |

| Females 45 years and older | 1 |

This record accounts for Melchior and his wife and youngest three children. The three oldest sons had already married and moved away. However, the son's age is wrong again; by this time Peter was seventeen years old.

John Melchior Plank was still a poor man in 1803, the last year in which he was taxed in Lancaster County. He owned two horses and three cattle. Perhaps by this time he was ready to retire from active farming and to stay with his children on their farms.

His Children

While Melchior and Margaret Plank were living in Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County, their children began to scatter:

While Melchior and Margaret Plank were living in Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County, their children began to scatter:

Jacob (Nov. 6, 1767-Jan. 10, 1851) married Mary Yoder (Feb. 13, 1771-Mar. 28, 1850) in 1791 and moved to Mifflin County in 1795. He received a warrant for a tract of 150 acres in Union Township in 1796. Later he purchased more land adjacent to the initial tract and built an oil mill. Jacob and his sons stayed in Mifflin County until 1821, when they moved to Wayne County, Ohio.25

Christian2 (1771-Mar. 4, 1851) married Barbara Yoder (June 20, 1766-Apr. 13, 1850) in 1792 and moved to Earl Township in Lancaster County, where he bought a tract of 12 acres in 1803. In 1813 he sold this land and moved to Strasburg Township, where he farmed as a tenant for a few years. In April 1816, perhaps the month his father died, he bought 101 acres of land near his brother's land in Union Township in Mifflin County. He later bought more land there and stayed there the rest of his life.26

John (1774-1824 or 1825) married Magdalena Yoder (b. 1778) in 1799 and moved to Mifflin County beside his brother. According to family tradition, Mary, Barbara, and Magdalena were sisters. About 1804 John moved to Huntingdon Township in Huntingdon County. He moved to Somerset County about 1812 and to Coshocton County, Ohio, in what is now Holmes County in 1818.27

Barbara (b. 1776) married a man named Miller. Her life and descendants have not been traced.

Margaret (b. 1779) was named in Melchior's will with the surname of Hurting. This may have been a variant spelling of Harting (Horting, Hortung, Harding) or a variant of Hertig (Herring).28 Her life and descendants have not been traced.

Peter (June 1, 1783-June 8, 1848) married Rachel (Feb. 15, 1784-Mar. 16, 1864) before 1808 and settled in Earl Township in Lancaster County, where he stayed as a tenant farmer.29

His Last Years

After retiring, John Melchior Plank apparently moved to Cumru Township in Berks County. Perhaps one of his daughters or other close Amish friends lived there. The name "Melcher Planck" was squeezed into the appropriate place on an 1807 tax list. He was charged with a tax of fifteen cents. The 1810 United States census found him living in Cumru Township with his wife.30

Melchior and Margaret Plank moved to Mifflin County in 1810 or 1811 to live with their oldest son, Jacob. Historians who thought they moved to Mifflin County before 1800 were clearly mistaken.31

On November 1, 1811, the will of "Milchior Plank" of Union Township in Mifflin County was signed with his mark (X). He willed all of his estate to his wife, Margaret, during her life. After her decease the remainder was to go to Jacob or his heirs. Each of the other children was to receive one dollar.32

The date of Melchior Plank's death is not known, but his will was filed on April 16, 1816, in the Mifflin County Courthouse at Lewistown, where it remains. The next day the will was proved upon the oaths of two witnesses. On April 25 Jacob was affirmed as executor and was issued letters of administration with a copy of the will. This copy, penned by the register, David Reynolds, was passed down through the family along with the indenture paper. They are now deposited in the Archives of the Mennonite Church in Goshen, Indiana.

Conclusion

The following four points summarize the evidence that Melchior Plank and Johan Melchior Blankenberg were the same person.

- The Blankenberg indenture was handed down in the Plank family along with the copy of the will which had been issued to Melchior's executor in 1816. No evidence exists that it came from another source.

- The earliest documentary evidence of the use of the name of Melchior Plank shows that in 1774 he lived only a few miles from the place where Blankenberg was set free in 1772. If Blankenberg was not Plank, he disappeared without a trace.

- Tax lists of Caernarvon Township in Berks County and Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County show that Melchior Plank was known by the name of "John." The 1790 United States census record for Caernarvon Township in Lancaster County, when compared with the tax list, proves that the same person was known as "John" and "Melchior." Naming an oldest son after his father was common among the Amish at that time. However, none of Melchior Plank's sons had a son named Melchior. Three of Melchior's sons -- Jacob, Christian, and Peter -- named their first sons John. Melchior's other son, John, named his second son John. This may provide evidence that Melchior was known as John.

- Plank family traditions agree in many points with the immigration and indenture record of Blankenberg. He sailed from Rotterdam to Philadelphia, was sold to pay his passage, and purchased his freedom before his term was finished.

Many aspects of the tradition are unproved. The origin of Plank or Blankenberg in Europe remains unknown, and even the surname which he used in Europe is in doubt. If he was from a non-Amish Blankenberg family, the story of how he came to join the Amish and shorten his name would be interesting. If he was from an Amish Blanck family, we would like to know why he used the name Blankenberg in 1767. Was the story about the nautical kidnapping an incident that really happened, or did the story evolve as a way of answering questions which the family felt to be embarrassing? Was Margaret bound to another master, or did she win her freedom earlier? Did Plank work for Morgan during the Revolutionary War?

Many of these questions will never be answered. However, some documents which could help to complete the story may be found. According to a news story from 1898, Melchior Plank's family Bible was then owned by Jacob Miller of Weilersville, Ohio.33 Isaac Jones, Jacob Morgan, and Joseph Millard had docket books which could confirm the Blankenberg indenture and reveal an indenture record for Mrs. Blankenberg. Personal records in the Cloud, Hughes, Rickenbach, Hertzler, Morgan, and Clymer families may mention servants, hired workers, and tenants. Miller and Hasting family records may help to identify Melchior Plank's daughters. Various possibilities for research in Europe exist. I hope this article will stimulate and encourage other interested researchers to make further contributions to the reconstruction of the life of Immigrant John Melchior Plank.

[Footnotes]1

- The indenture, the copy of the will, and other papers, letters, account books, and related materials were donated to the Archives of the Mennonite Church, Goshen, Indiana, by Ina K. Plank. This collection is kept in five boxes. John F. Murray in "Blank/Plank Ancestry of the Amish Mennonite Tradition," Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage 4 (July 1981): 17, suggested that the indenture and other documents were taken from courthouses. This is unlikely. Indentures are personal property. Papers in the collection include an essay entitled "History of the First Plank's That Came to America" and written in or before 1952 by Harvey C. Plank. This essay shows familiarity with the indenture, and the papers include a list naming his widow, Clara Belle (d. 1957), as the owner of the indenture.

- Articles written by persons outside the family sometimes misunderstood the tradition and referred to Melchior as a "native of Rotterdam." See Commemorative Biographical Record of Wayne County, Ohio, Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens, and of Many of the Early Settled Families (Chicago: J. H. Beers, 1889), p. 152.

- Dr. D. Heber Plank of Morgantown, Pa., found Melchior Plank's name on old tax lists and concluded that he was Michael, the brother of Amish Bishop Peter Plank. He then repeated a story his father had told him about "said Melcher or Michael (as the case may be)." The story was in fact about Michael. See Dr. Plank's notebook or "Journal," pp. 29-30, 100, owned by Adeline Plank of Morgantown. Dr. Plank, C. Z. Mast, and others tried at times to connect the Planks and Delaplanks/De la Planks of Berks County, Pa.

- This information is given in E. E. Plank, Descendants of David H. Plank (Canyon, Tex.: 1964), p. viii.

- The oldest known version3 written by a family historian was by David Herr Plank of Garden City, Mo., in 1898 for the Plank Reunion at Wooster, Ohio. See Plank, Descendants of David H. Plank, pp. viii-ix.

- Ralph Beaver Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers: A Publication of the Original Lists of Arrivals in the Port of Philadelphia from 1727 to 1808, ed. William John Hinke (Norristown, Pa.: Pennsylvania German Society, 1934), 1:718.

- This date is found by subtracting his age at death from date of death, both of which appear on a tombstone in the Plank Cemetery in Wayne County, Ohio. However, tradition says Jacob was born in 1768.

- The name is Edward, not Howard, Hughes. Perhaps Ina K. Plank misread this name on the indenture, and the mistake has been repeated in the Plank article (Mennonite Encyclopedia, s.v. "Plank," by Melvin Gingerich) and in Plank, Descendants of David H. Plank.

- The land farmed by Jason Cloud, Jr., is mentioned in the will of Jason Cloud, Sr. (Will F-396 [no. 3924], Chester County Courthouse, West Chester, Pa). The land is fully described in Deeds R-1-366, S-1-278, and E-2-98, Chester County Courthouse, West Chester, Pa.

- See tax lists at the Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, Pa., filmed by the Genealogical Society of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- See Chester County Quarter Sessions docket, Chester County Courthouse, West Chester, Pa., for two cases. See also photocopy of clipping in Jacob Martin, Abstract of Wills of Chester County, Pennsylvania ([Philadelphia: Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, ca. 1980]): 3:72.

- Two men named Edward Hughes of Berks County must he considered as possible masters of Blankenberg because of their associations with Joseph Millard, Sr. However, they are less likely candidates because of their distance from Cloud and Morgan, their relative lack of wealth, and the lack of evidence that they possessed servants at the time.

- The December 1770 tax lists bear two signatures. Another signature is on Deed P-1-450, Lancaster County Courthouse, Lancaster, Pa., where Hughes signed in the margin as a satisfied mortgagee. Other information about Hughes is from land warrants and several deed records and orphans' court records.

- See tax lists at Lancaster County Historical Society, Lancaster, Pa., filmed by the Division of History, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pa.; Pennsylvania Archives, 3rd ser., XVII, 30.

- Pennsylvania Archives, 3rd ser., XVII, 301, 350.

- A loan was made to Hans Schantz to pay for "sein Fracht," or ocean passage, in 1774. A facsimile copy of the page containing this entry appears in The Diary 9 (September 1977): 207.

- Deed book 9, pp. 4-6; Inventory, 1774; Account, 1784; Will B-1-58; Orphans' Court, book 3, pp. 110, 126, Berks County Courthouse, Reading, Pa.

- These tax lists are at the Historical Society of Berks County, Reading, Pa., and were filmed by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pa.

- This eliminates the possibility that these entries refer to any of the other known men named John Plank/Blank. All four of them were landowners residing in Cocalico and Salisbury townships in Lancaster County.

- Morgan did the same thing to the name of Melchior Schweitzer, also a new resident of the township. He was familiar with the name Malachi because of Malachi Jones, another resident.

- C. Z. Mast, "Old Settler Stories: The Plank Family," Christian Monitor 15 (October 1923): 309. This was the Morgan who signed the indenture. He was addressed as Colonel from 1777. See his biography and signature in Morton L. Montgomery, Historical and Biographical Annals Embracing a Concise History of the County and a Genealogical and Biographical Record of Representative Families of Berks County, Pennsylvania (Chicago: J. H. Beers, 1909), 1:355-356.

- Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790: Pennsylvania (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908), p. 127.

- Deeds Q-1-532 and W-3-565, Lancaster.

- "Population Schedules of the Second Census of the United States," 1800 (Lancaster Co., Pa.) [microfilm], roll 39, p. 92. Two men correctly named Michael Blanck were also listed that year in Pennsylvania.

- The tradition articulated in Plank, Descendants of David H. Plank, p. ix, gives Jacob's birth date as 1768. Calculations based on cemetery records, according to Wayne County, Ohio, Burial Records (Wooster, Ohio: Wayne County Historical Society, 1975), p. 639, providing date of death and age at death show Jacob's birth date as November 6, 1767. Mary's age at death is incorrectly given as 79 years, 1 month, and 5 days in the same source, but on the gravestone in the Plank cemetery in Wooster, Ohio, and in Commemorative Biographical Record of Wayne County, Ohio, p. 152, her age is given as 79 years, 1 month, and 15 days.

- lnformation taken from Lancaster County and Mifflin County tax lists; Deed book 7, vol. 4, pp. 41, 497, Lancaster; Deeds M-210, R-330, R-332, Mifflin County Courthouse, Lewistown, Pa.; Will 3582, book 4, p. 312, Mifflin County Courthouse, Lewistown, Pa. Christian lived in the northern part of present East Earl Township in Lancaster County. Strasburg Township in Lancaster County then included what is now Paradise Township. Dates for Christian and Barbara Plank are based on cemetery records. See The Cemeteries of Mifflin County, Pennsylvania (Lewistown, Pa.: Mifflin County Historical Society, 1977), p. 933.

- See Murray, "Blank/Plank Ancestry": 17-18; "Third Census," 1810 (Huntingdon County); Mifflin County tax lists. Leroy Beachy, Cemetery Directory of the Amish Community in Eastern Holmes and Adjoining Counties in Ohio ([Millersburg, Ohio: Compiler], 1975), p. 102, states that John Plank's will was dated August 5, 1824, and was probated in May 1825. The tradition articulated by Plank, Descendants of David H. Plank, p. 1, gives 1774 as John's birth date. Hugh F. Gingerich, "Amish Yoder Families in America," The Diary 14 (March 1982): 77-78, note A(10), provides Magdalena's birth date, and, after accepting the three-sister tradition, concludes that these sisters' father was Yost Yoder, father of Christian Yoder (b. 1761).

- See Melchior Plank's will, no. 3692, Lewistown. The copy is recorded in will book 2, p. 260.

- Information from Lancaster County tax lists. Rachel purchased a house with a tract of 1 7/8 acres along the Hinkletown-New Holland road in 1849 and lived there until she died in 1864. See unrecorded deed no. 3899½, Lancaster. Peter's and Rachel's dates of birth and death are taken from the gravestones at Trinity Lutheran Cemetery, New Holland, Pennsylvania. Dates of death for both Peter and Rachel also appear in Accounts and Reports, book 19, p. 61, and also in Deed K-9-46, Lancaster.

- See tax lists for Berks County, Pa., and "Third Census," 1810 (Berks County) [microfilm], roll 45, p. 701.

- After studying some tax lists in 1903, Dr. D. Heber Plank of Morgantown wrote that Melchior Plank moved to Mifflin County, Pa., about 1793. When C. Z. Mast wrote his 1923 article about the Plank faniily (see footnote 20), he received help from Joseph K. Plank of Orrville, Ohio, a descendant of Melchior's son Jacob. Evidently Mast mistakenly applied to Melchior some facts concerning Jacob. Mast wrote that Melchior moved to Mifflin County in 1795. However, that was the year Jacob moved. Mast wrote that Melchior died at age 83. No other evidence exists for this information. However, we know that Jacob died at age 83. John F. Murray, a descendant of Melchior's son John, wrote that Melchior's entire family moved to Mifflin County in 1799, when John moved. See John F. Murray, A Family History of Murrays, McKibbins, Smiths, Planks, Neffs, and Related Families of Elkhart + Lagrange Co's. [sic] in Indiana (Kouts, Ind.: 1977), p. 84.

- Will no. 3692, Lewistown.

- Wooster (Ohio) Republican, Sept. 28, 1898, supplement.