Back when it was fun

When city editors like Aggie Underwood ruled the nation's newspapers

BY BILL WALKER

![]() ggie Underwood, legendary city editor of the old Los Angeles Evening Herald-Express, sometimes used a baseball bat to enforce her will upon reporters in a city room that always seemed to reek of cigar ash, printer's ink, stale whiskey, and cigarette smoke.

ggie Underwood, legendary city editor of the old Los Angeles Evening Herald-Express, sometimes used a baseball bat to enforce her will upon reporters in a city room that always seemed to reek of cigar ash, printer's ink, stale whiskey, and cigarette smoke.

I'm one of those who endured the occasional lash of her profane tongue. But few of the reporters who worked for her will deny that she was one of the great city editors of her time. Aggie ran the city room when it was still fun to be a newspaperman.

City rooms aren't the same these days. No smoking. There's carpet on the floor. No stentorian voices bellowing "Copy boy!" And it's so quiet you could be in a bank or the city morgue.

City editors have simply vanished on many newspapers. Now they're metro editors. One large West Coast newspaper revamped its newsrooms and abolished department editors.1 Instead of city editors they have team leaders. And newsroom managers.

Team leaders? Stanley Walker (New York Herald-Tribune) would spin in his grave. Aggie would grab her bat, punctuated by some choice profanity. That title would drive martinet James H. Richardson (Los Angeles Examiner) back to the bottle he had to foreswear after boozy years as city editor and managing editor of two other Los Angeles papers.

Underwood was one of seven city editors for whom I worked as a photographer for 24 years. For better or worse we were beholden to those talented, fiery, sarcastic, often alcoholic, knowledgeable overseers who drove their slaves at a frantic pace.

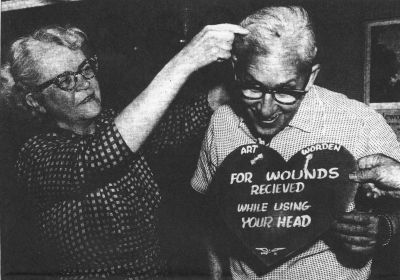

Aggie Underwood, the spunky city editor of the Her-Ex, gives Art Worden a "purple heart" for an injury while in action.

And while Aggie could use a baseball bat sometimes to enforce her will, Harold "Hal" Fetter used other tactics. When I went to the Her-Ex in 1940, two months out of university, Fetter was city editor. Wiry, slight in stature, with a mop of curly hair, Fetter had a voice that could cut like a knife through the city room when he was displeased. The consummate city editor, he wore a green celluloid eye shade, a remnant of the copy desk. He had been telegraph editor and then traded jobs with Cappy Marek.

Fetter was hot-tempered and drove the newsroom at a frantic pace, which included at least six daily editions. He had a taste for language. As a take-charge editor, he exuded confidence in how to get the job done - his way. Fetter got onto one reporter's back so hard, so often that the target laid strong hands on Hal's shoulder and threatened him with third-floor defenestration to the cobblestone alley below. Managing Editor John Bayard Campbell intervened and told Jack Hereford: "Apologize to Mr. Fetter." Hereford refused and was summarily fired.

Three years later, Fetter got into a nasty shouting match with Campbell, whose chair was six feet away. Fetter ended the noisy confrontation by telling Campbell to "take this paper and shove it!" He put on his hat and coat and walked out, leaving a stunned newsroom just as the second edition deadline was met. Fetter worked as a movie studio publicist for a brief stint and then returned to newspapering as first-edition editor of the morning Examiner.

Fetter's predecessor was Arthur (Cappy) Marek, whose nickname derived from World War I service in France as an artillery captain. He had been a competent, all-around reporter when named city editor in the 1930s. He was a fashion plate, always flawlessly dressed, and sported a silver-handled Mallaca cane to ease his limp. He liked his cigar, a glass of whiskey, and the colorful crew of winos, drifters, reporters, bar flies, photographers, whores, and circulation drivers who frequented Moran's, the watering hole for Herald employees.

Cappy looked on life as one continuous joke and his wry sense of humor shone when he staged a grand re-opening party for a rebuilt Herald men's room. Underwood recounted it in her memoirs "Newspaperwoman": "The premiere included sandwiches and cake from a caterer, a small brass band, film stars, with actor-comedian Doodles Weaver as master of ceremonies and comedian Red Skelton cutting the obligatory ribbon."

Marek made one inspired choice in 1935 when he hired Underwood from the Evening Record where she was a top reporter. Marek as city editor was tired of being scooped by Underwood. The salary increase prompted Underwood to make the change. The Record was on its last legs, soon to be swallowed by the Daily News. Ironically, 12 years later, Underwood replaced Marek as city editor.

In her stint on The Record and 12 years on The Herald, Aggie had covered every type of story, including train and plane crashes, gangland murders, disasters, Hollywood scandals, divorce court, murder trials and even the last gallows execution at San Quentin Prison.

After Fetter's stormy resignation, Managing Editor Campbell rotated city editors. Lou Young had served time on the police beat, rewrite, and several years as Marek's desk assistant. Jack Berger was a veteran of general assignment and rewrite on The Herald after stints as city editor of the Los Angeles Times, the Los Angeles Examiner, and The Associated Press in San Francisco. Young would be city editor two weeks and then move over one chair and give Berger the hot seat.

Intense, concentrated, a no-nonsense type, Berger worked every assignment no matter how small as The Story Of The Day. As city editor he was solicitous of cub reporters and photographers; he made it his business to see they didn't get trampled on.

Reporter Cleve Hermann, who toiled in the city room under Fetter and then Young and Berger, recalled a typical Berger anecdote.

Don Ryan came to The Herald during World War II after a successful career as a screenwriter, adapting his novels. One day Ryan went to Berger's desk and announced he had tried to commit suicide that morning. Berger didn't even look up from the pile of copy he was editing, but politely asked Ryan what method he used.

"I drove my car into the garage," Ryan said, "closed the door and, with the motor still running, tried to go asleep on the front seat."

"What happened?" Berger asked.

"Obviously it didn't work," Ryan replied. Berger nodded his head in sympathy and replied, "That's the trouble with this wartime gas we're getting. It isn't worth a damn!"

The rotating city-editorship ground to a halt in fall 1946 when the American Newspaper Guild called a strike and closed the paper for three months. When the strike ended and publication resumed, Lou Young had left for a Burbank paper and Berger was sole city editor. Three months later he quit to become managing editor of the Valley Times, a small suburban daily.

Marek then moved over from the telegraph desk as city editor again. This time he had a new assistant - Aggie Underwood. But the pressure on Cappy was too much. He drank heavily and Campbell fired him. Campbell, who was notorious for devouring city editors, then tapped Aggie on the shoulder and pointed. "You sit there." "There" was the city editor's oak swivel chair.

One well-traveled newsroom wit once compared that oak chair in The Herald city room to similar chairs he had seen in Huntsville, Texas, and Sing Sing, New York. There was a subtle difference. Those oak chairs were bolted to the floor and each boasted heavy ankle straps to restrain the unlucky occupants from writhing about too much.

It was a perilous job, being city editor at The Herald, because Managing Editor Campbell had been city editor for seven years. Campbell started as a waterfront reporter on the San Francisco Chronicle, was beaten up by dockside goons, and shot once while enjoying whiskey in a neighborhood saloon.

When the owners of the Los Angeles Herald decided to switch from morning to evening publication in 1911, they hired Campbell as first city editor where he ruled with an iron fist. Herb Krauch described his first visit to the Herald news room in 1912. Campbell was in a fist fight with his city hall reporter. Krauch decided that would be a great place to work. Forty years later he succeeded Campbell as managing editor.

Campbell went up the ladder: news editor, assistant managing editor, and then managing editor for 21 years. His swivel chair was at the end of the copy desk, with the wire editor five feet away to his left and the city desk six feet right. Campbell would stalk from his glass-enclosed office through the city room, a cigar in his mouth, a lion, the uncontested king of the jungle, in the words of Cleve Hermann. He once told Hermann, "You can't put out a good newspaper unless you're good and drunk? And he had a bottle of whiskey in his office for a frequent afternoon nip.

When Krauch retired in 1963 after nine years as managing editor of the largest evening newspaper in America, he said the smartest thing Campbell ever did was to name Underwood city editor. And she defied the jinx on city editors, holding the post for 17 1/2 years.

Aggie survived seven years with Campbell, nine years with Krauch, and almost two years with John Denson, former editor of the defunct New York Herald-Tribune, and then Bud Lewis, her contemporary on the L.A. Times. The fifth managing editor, jealous of Aggie's fame and persona, "promoted" her to assistant managing editor and banished her to a small office with no specified duties.

Aggie was a clear-eyed, striking woman and in her years on the desk she blazed a path for women as editors. She was the first woman city editor of a major metro daily. She had the time and the personality to build a strong, loyal crew of photographers and reporters, and backed them to the limit, as long as they were honest with her. She knew all the excuses. She knew the city and the county from 15 years on the street.

She could remember a favor as well as a slight, and heaven help anyone who got in her bad graces. Working for her was a daily adventure, punctuated by eight editions. She ran the city desk as her own show.

In her 1948 biography "Newspaperwoman," she related one story that showed she could operate a city desk under pressure without blowing up. A chemical plant explosion rocked downtown Los Angeles about 10 o'clock one morning. There were dozens dead, square blocks of utter devastation and mass confusion. Aggie kept on top of everything, organized crews of photographers and reporters, and fed takes to the copy desk. The press run that day and the next was over a million copies.

drastic changes were due in the way the Los Angeles Police Department dealt with the working press or else.

Hizzoner got the message. He called in Police Chief William Parker and in front of the angry editors told him quite bluntly that if the railroad/press fiasco ever happened again, Parker would no longer be chief.

Parker understood. He appointed a press liaison officer with full authority to deal with the media. Inspector Ed Walker, 6 feet, 6 inches tall, with broad shoulders and an imposing physical presence, outranked divisional/precinct captains and had direct authority to deal with the press.

Relations improved immediately. If working press members had trouble with an officer and couldn't solve the impasse on th scene, they simply informed Walker of the officer's badge number. Then would come the invitation: report to Inspector Walker at city hall. End of problem.

When Aggie was suddenly shoved aside as city editor, she was replaced by Tom Caton, who had toiled 11 years as her assistant. He was a big, physical specimen, never without a cigar clenched between his teeth, and had learned the virtues of patience and city room politics.

In his younger days as a Times reporter, Caton had covered many of the general assignment stories that Aggie covered. Then he got the prize beat job: Covering the district attorney and criminal courts. Caton liked his grog and could get progressively meaner as the whiskey flowed. And there were plenty of saloons around civic center and the Times to slake a newsman's thirst.

Caton's pals were a boisterous crew -- Sid Hughes, who had worked on the Record, Herald-Express, Examiner and, finally, on the new tabloid Evening Mirror; Casey Shawhan, a former halfback at USC who worked on the Examiner and Times before a stint as first city editor of the Mirror; and Gener Sherman, a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter on the Times.

Grog and deadline pressure spelled a recipe for brawls, and this quartet of well-endowed specimens had their share.

Shawhan once described to me a bleary evening in a saloon near city hall when a robbery squad detective, cordially disliked by all hands, tried to break up an argument Caton and Shawhan were having at the bar, separated by only one stool. As the rhetoric and whiskey heated up, the cop tried to intervene as peacemaker. Caton and Shawhan swung at each other as if synchronized, and the dick took a belt on both cheeks that required treatment at Georgia Street Receiving Hospital. Meanwhile the crafty journalists were buying each other another round -- the whole squabble was a setup to punch out an obnoxious, nosy cop and make it look like an "accident".

A nasty, bitterly contested divorce with his first wife drove Caton out of town and up to the Portland Oregonian for two years as a general assignment reporter and a year as night city editor. Roy Wolf, the paper's chief editorial cartoonist, told how Caton would sometimes relieve newsroom pressure as the home edition was stitched together, lighting tiny firecrackers all over the city room.

In the fall of 1948 Caton ended his exile in wet, rainy Oregon and returned to Los Angeles, now to the Her-Ex. A brand new tabloid, the Mirror, was gearing up to give the Herald and the Daily News afternoon competition. This time Caton was competing against his old saloon pal from Times days. Casey Shawhan had been named first city editor of the new paper.

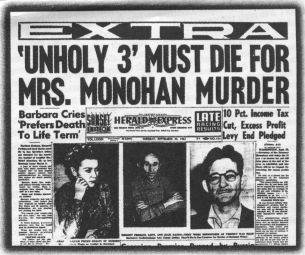

Caton worked as a top assignment reporter for five years; his specialty was covering capital murder trials. His last big case was the trial of Barbara Graham for the brutal murder of wealthy Burbank widow Mabel Monohan. Graham and her two cohorts died in the San Quentin gas chamber for that botched evening. When the trial ended Caton went on the city desk. And then 11 years later he replaced Underwood.

A year after the Herald-Express swallowed the morning Examiner to become the Herald-Examiner, the editorial duo of Krauch and Underwood, had, in early 1963, boosted the circulation to 735,000, the largest evening circulation in America. But in these days of MBAs and assistant managing editors by the dozen, do you think these two could get a job on any newspaper? Don't be foolish. Neither had a master's in journalism. Nor did either one even attend college. Aggie's formal schooling stopped at the eighth grade!

Caton's reign as city editor lasted almost 14 years before he retired in the late '70s. His first-hand trial experience at the grimy old Hall of Justice in covering murder trials in the '40s and '5Os was put to the ultimate test as he directed coverage of two "Trials Of The Century" that preceded the 1995 O.J. Simpson murder trial. They were the trials of Sirhan Sirhan for the assassination of Sen. Robert Kennedy in 1968 and the trial of murderous Charlie Manson and his gang of blood-lusting hippies in 1969-70.

Caton died in 1991; Aggie, who had retired in 1968, died of a heart attack in Colorado in 1984; Krauch, who died in 1992, at 96, was the acknowledged dean of Los Angeles editors.

The last city editor I worked for was a quiet, slender, low-key veteran of the Hearst wars, Harry Morgan, who came to the morning Examiner in the 1920s. Morgan, along with several other reporters who migrated to Los Angeles, had worked in El Paso, covering the border forays of Pancho Villa and his choice for presidente, Venustiano Carranza. Morgan, ex-city editor Cappy Marek, and Ray Hanners, who covered the federal courthouse for the Los Angeles Daily News, had worked with and for my uncle, Norman Walker, the flamboyant city editor of the El Paso Evening Herald, who later became an Associated Press bureau chief.

Morgan had probably the longest tenure of an Examiner editor. He was night editor for decades and learned to deftly field calls from the chief himself, Publisher William Randolph Hearst, who from his study atop San Simeon Castle second-guessed his herd of editors.

Will Fowler gave Morgan extensive coverage in his 1991 memoirs, "Reporters," and remembers Morgan as "the kindest and most teaching editor I ever knew."

Morgan, in his quiet, unhurried way, unflappable after 30 years of talking to the Chief, was a complete master of the news desk. I knew him in the last five years of my 27-year span; he was the Saturday-Sunday city editor, after the two papers merged in 1962.

He was a complete contrast to huge, gruff-voiced day city editor Tom Caton, never without his cigar.