At Last, Bound for Glory

100 Years After Debut, Legacy of 'Big Train' Finds Home in D.C.

By Barry Svrluga

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, August 1, 2007

When he stepped off the train from Idaho, there is every indication Walter Johnson meant to record each of his accomplishments in the District, where he would transform from hayseed to historic figure. Scribbled in the notebook section of a scrapbook he cobbled together are the beginnings of the story: "Arrived D.C., July 26, 1907."

Yet there is no other entry. History, it seems, would be left to others. And when baseball left Washington, part of Johnson's legacy left, too. At Yankee Stadium, Babe Ruth's memory is kept alive in Monument Park. Ted Williams's No. 9 will never come down from the facade on the upper deck in right field at Fenway Park. Even places where major league baseball arrived within the last half-century -- Minnesota and San Diego and Seattle -- have public displays honoring past heroes.

Washington's history is murkier. One hundred years ago tomorrow, Walter Johnson -- one of the greatest pitchers ever to step to the mound -- threw the first of his 802 major league games, all in the uniform of the Washington Senators. But when the Senators departed the city -- not once, but twice -- in the 1960s and '70s, Johnson's legacy had no place to thrive.

"It was," said Carolyn Johnson Thomas, one of Johnson's six children, "a cultural loss."

"The Big Train," as he came to be known not so long after that first start against the Detroit Tigers, lived in the District, then Bethesda, then out in Germantown. Carolyn Thomas has lived in the same house in upper Northwest for 52 years, raising her own family there. And for years, perhaps the best history of her father the legend resided in the bottom cupboard of a built-in bookcase, behind a sign hanging from one of the knobs that says, "A spoiled-rotten West Highland Terrier lives here."

There sit perhaps 30 scrapbooks of Johnson's career, assembled by his wife, Hazel. Faded and curled newspaper clippings, some photos, accounts of so many of those 417 wins, those 531 complete games, those 110 shutouts.

For years, those family scrapbooks served as the District's best record of Johnson's accomplishments. Eventually, Thomas's son Henry -- "Tom" to his mother, "Hank" to his friends -- fished them out, began reading them over. He had a degree in accounting and ran nightclubs in Georgetown. He grew up a baseball fan and walked by the statue of his grandfather that once stood outside Griffith Stadium, long since demolished. But he had never connected with his own lineage. In the late 1970s, with no baseball in Washington, that changed.

"It started as a hobby," Hank Thomas said. "I would come over, and for several years, it was like a library. I'd take a couple of scrapbooks and bring them back."

The Baltimore Orioles, with their own heroes and own history, were the closest team to Washington then. With each passing year, fewer people who had seen Johnson pitch -- he lasted 21 years with the Senators, the hero of the city's only World Series champion, in 1924 -- remained in town, or on earth. Hank Thomas kept reading those scrapbooks and began taking notes on 3-by-5 index cards.

"There hadn't been any interest in him for years," Thomas said. "There wasn't a team. I think interest in baseball history had waned a little bit. This wasn't quite the big deal that it had been for my generation."

Johnson died of brain cancer the year Henry Thomas was born, 1946. The only interaction between the two that Carolyn Thomas can remember is when she went to the hospital to see her father. She was told he was in a coma. Yet when she arrived, he said, "How's that fine baby boy?"

And eventually, Walter Johnson became an obsession for his grandson. Those trips through the family library grew into the book, "Walter Johnson: Baseball's Big Train." Henry Thomas wrote it, in large part, because with baseball gone from Washington, no one else would.

"I think I've got a good fix on him, on who he was and what he was like," Thomas said. "But I'd still like to sit down with him for 10 minutes -- just to get the flavor."

'The Most Powerful Arm'Ty Cobb later recounted the moment in his autobiography. "On Aug. 2, 1907, I encountered the most threatening sight I ever saw on a ballfield."

Yet early that day, Cobb and the rest of the Detroit Tigers didn't think much of Johnson as he warmed up for the second half of a doubleheader. The kid from Kansas was 19, had been pitching in a place called Weiser, Idaho, and was being rushed into the rotation of a last-place club by Manager Joe Cantillon. He had an unorthodox, slinging motion in which the ball seemed to come from behind his body. Cobb recalled that "we licked our lips" at the prospect of facing him.

"One of the Tigers imitated a cow mooing and we hollered at Cantillon: 'Get the pitchfork ready, Joe -- your hayseed's on his way back to the barn,' " Cobb wrote.

They were wrong. Johnson didn't win that day, leaving after eight innings in which he allowed six hits -- three of them infield scratches -- and two runs. When he was lifted for a pinch hitter in the eighth, he was headed for the first of his 279 losses. But he had left his mark.

J. Ed Grillo, covering the game for The Post, wrote: "Walter Johnson, the Idaho phenom, who made his debut in fast company yesterday, showed conclusively that he is perhaps the most promising young pitcher who has broken into a major league in recent years. . . . He had terrific speed, and the hard-hitting Detroit batsmen found him about as troublesome as any pitcher they have gone against on this present trip."

Indeed, the Tigers were wowed. They were on their way to the American League pennant and had a fearsome lineup. But after they swept the doubleheader by beating Johnson in that second game, they knew they had seen a man who would be a rival for years.

"I watched him take that easy windup -- and then something went past me that made me flinch," Cobb said. "I hardly saw the pitch, but I heard it. The thing just h issed with danger. Every one of us knew we'd met the most powerful arm ever turned loose in a ballpark."

Twenty-nine years later, Cobb and Johnson would be two of the five members of the first class inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y. Last weekend, fans clustered around their plaques. Johnson's reads, in part, "Conceded to be fastest ball pitcher in history of game."

For the 33 summers baseball was absent from Washington, that is where Johnson's legacy lived. His family remained here.

Baseball Stays in the FamilyEvery night there is a game, the television flickers in the Thomas house in Northwest Washington. "They're all my boys," Carolyn Thomas said. "Every single one of them."

She is speaking of the Washington Nationals, the last-place club that has replaced not only her father's Senators, but the expansion version of the Senators that followed into town when the original version departed. At 84, she is a shrewd fan of the sport and the team, wondering when first baseman Nick Johnson will return from his broken leg, wondering if pitcher John Patterson's arm will every fully recover.

"I love it," she said. "I'll tell you, I say of the Washington Nationals: The Nationals, they're better than they look. They are. They are. They're a fine team. They're going to be in the playoffs within the next few years."

For the girl who "grew up at Griffith Stadium," those are weighty words. Yet tomorrow, she will travel across town to RFK Stadium for the first time since the Nationals arrived here in 2005. She doesn't like publicity, she said, and doesn't particularly enjoy being out at night. Plus, that leaves Bonnie, her dog, home alone.

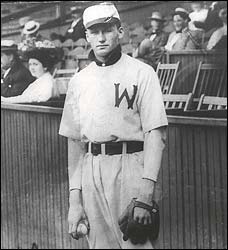

Walter Johnson's grandson believes that this is the first photo taken of Walter Johnson in a Senators uniform. (Courtesy of Henry Thomas)

The Nationals, though, are hosting Walter Johnson Day. Hank Thomas, now living in Arlington and the owner of a sports memorabilia business, will travel back from a major show in Cleveland to throw out the first pitch. The Nationals will wear replica Senators hats from 1927, Johnson's last season. There will be video highlights, a pregame ceremony.

Perhaps some of the memories will flood back to Walter Johnson's daughter, just being at the ballpark. She has a brother, Eddie, who lives on a farm in Montgomery County. She has a small den in her home that Hank has decorated with all sorts of Johnson photos.

And now, she has the Nationals, baseball back in her home town. The club will open a new ballpark next year, and there are plans for three statues outside -- one for Josh Gibson, the great Negro leagues catcher; one for Frank Howard, the "Capital Punisher" of the expansion Senators; and one for Walter Johnson.

"Dad was just 'Dad,' " Carolyn Thomas said. "I think he was a good role model, and I think in this steroid age with asterisks and one thing or another, it's good to remember the nice guys."

Tomorrow, 100 years after he threw his first pitch here, Washington will finally remember a nice guy, one who might have been forgotten in his adopted home town had baseball not returned.

Staff researcher Julie Tate contributed to this report.