GREAT MYSTERY IS SOLVED!

Science Finds That Worm Inside Mexican Jumping Bean Causes Antics in Quest of Shade

BY NORMAN WALKER.

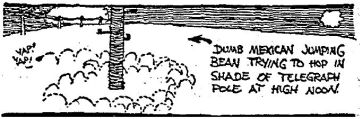

Science has at last explained why the Mexican jumping bean jumps. After exhaustive studies of the flopping frijole, Mexican scientists have finally concluded that the jumping bean jumps to get out of the sun and into the shade of the nearest shade-producing object.

JUMPING BEAN IS SUN DODGER

With the love of shade so characteristic of the Mexican, which makes him seek the shady side of an adobe house until be has made tracks around the building as the sun wheels its course in the sky, the jumping bean, or rather the worm within the bean, which acts as a propelling force, makes a desperate effort to find the shade. His restricted efforts within the bean give the peculiar jumpy motion to the bean when exposed to heat. It is denied, bowever, the worm within the jumping bean is the hookworm as it is known to American science since it does show some signs of animation.

WILL DO JAZZY DANCE

Curio dealers do a big business in Mexican jumping beans when they are in season. Placed under a strong electric light, where the heat will cause the worm to jump, the beans do a jazz dance as long as the light burns and the heat impels them in their efforts to find a shady spot where they may be comfortable and may lay their eggs with the assurance that they will hatch and make a new generation of jumping beans possible.

Jumping beans and resurrection plants are not the only commodities which Mexico supplies the American curio dealers in commercial quantities. The armadillo, armoured cruiser of the desert, gives up his coat of mail to supply the homes of the American tourists with ornamental baskets made from the shell, tail and head of these dry land turtles. They are caught on the desert, killed, their shells removed while the animal is still kicking and the tail bent to form the handle of the curio basket before it hardens. These armadillo baskets bring a good price on the curio market and hundreds of them are sold to tourists to take home as souvenirs.

Dressed fleas are always in demand. These little insects, which are so much a part of the Mexican home life, are caught young, killed, stuffed and dressed in typical peasant dress of the natives and are sold for 25 cents each, incased in a miniature display box. They are so small they must be seen under a microscope in order to appreciate the minute detail which the Mexican handicrafsmen attain in dressing these fleas. Wedding parties, the bride wearing a white satin dress with a train and the conventional orange blossom wreath, the groom looking foolish in a shiny black suit belonging to his father, are reproduced in detail until the only thing that is lacking is the miniature wedding ring.

WAX FIGURES SELL

Mexican waxwork figures also have a ready sale to tourists. The source of supply in El Paso is where Francisco Vargas, Jr., works all day over his workbench modeling the types of Mexican peons in wax. His father, the late Francisco Vargas, became such a master of this art that a set of his figures were made for the Mexican government and placed in the National Museum in Mexico City as typical of the manual skill of the native Mexican. Vegetable women going to market with their shallow bowl filled with radishes, lettuce, tomatoes and fruits are modeled true to life. The color of the vegetables is even shown and the ragged dress of the peddler is reproduced in perfect detail. Another favorite piece of the wax worker of Alameda avenue is the charcoal vendor who is so much a part of the streets of any Mexican city. He has his sack of charcoal on his back, his clothing and face are blackened with the dust from his wares and the beads of perspiration may be seen standing out of his face as a result of the violent exercise. Mexican horsemen mounted on fiery steeds and wearing the typical charro costume of tight trousers, bolero jacket and high hat, are also made by young Vargas, every characteristic of the costume being reproduced in infinite detail.

One of his favorite pieces is that of a Mexican Indian being attacked by a mountain lion. The Indian is mounted on a horse bareback and the muscles of the animal are cleverly shown as he resists the repeated charges of the lion while the rider is shown in the act of plunging a knife into the lion's body. The coloring of the mountain lion, the blood from the knife wound, the skin of the Indian and the markings on the pinto pony are worked out in the most exact detail and the wax work sells for $50 gold to the travelers.

Chihuahua dogs, the diminutive pups which are so popular with dog lovers, are bred in the small border towns and offered for sale in front of the hotels and at the stations where tourists may be found. These little dogs have a pop-eyed, stupid appearance which is accentuated by their long ears, sharp nose and diminutive body. They bring a good price and the expert in buying and selling Chihuahua dogs knows all of the markings of a thoroughbred, if there are any such animals.

One of the ways of telling whether or not a Chihuahua dog is genuine, for the peddlers will sell mongrels that grow up to be three feet tall, is to feel for the hole in the skull just over and between the eyes. Knowing this the Mexican nature fakers fasten a rubber ball with the end of a furniture nail protruding a quarter of an inch, to the skull of the animal when it is born and a hole is made which will deceive the buyer.

Even the poor old bulls that are killed in the Juarez bullring furnish souvenirs for the tourist. Their horns are cut off, polished and sold to hatracks to those who like that particular brand of household art.