Plain Tales of Newspaper Men

A CORRESPONDENT WHO

LIVED HIS COPY!

For Fifteen Years Norman Walker Followed a

Path of Blood in Mexico, Hobnobbing With

Bandits, and Advising Presidents.

(Chapter V)

STOPPING WRITING BOOK TO COVER MEXICAN BANDIT

WARFARE FOR THE ASSOCIATED PRESS.

By JACK F. DADSWELL.

THE FINAL edition had gone to press. Out in the street boys were shouting its screamer lines. Hurrying throngs of shop workers stopped, bought and hurried on. Others, too anxious to reach their homes, passed up the opportunity and wedged their way through the crowd into still more crowded street cars. THE FINAL edition had gone to press. Out in the street boys were shouting its screamer lines. Hurrying throngs of shop workers stopped, bought and hurried on. Others, too anxious to reach their homes, passed up the opportunity and wedged their way through the crowd into still more crowded street cars.

At the corners, motorists impatient to be moving, sounded their sirens to force traffic. Policemen's whistles sounded above the din of the rush hour.

Up in the Herald's editorial room Mark Sullivan was reading the comic page. Across the copy desk Eddy Robinson talked under his breath into the telephone transmitter, smiled at the words he heard, and subconsciously drew pictures of pretty girls on the blotter before him. After a time he hung up, sighed deeply, and walked over to the window to peer out at the rim of the San Antonio mountains where the sun gradually was creeping out of sight. He sauntered back to the copy desk having witnessed that spectacle on other "dog watch" days, and seated himself upon it.

"Seth Conway says he's done with the newspaper game for good," Robinson remarked.

Mark Sullivan shifted uneasily in his chair, flung down the paper and got up. "Say," he drawled, "I've heard that before. But it doesn't mean anything. A fellow never gets out of this game no matter how much money he makes at something else..."

"That idea is as old as you are, Mark," rejoined the other a little sarcastically, but at the same time smiling. "Believe me, when I get out I'm going to stay out!"

"If you do, it proves that you never were born to belong to the Fourth Estate. When a fellow belongs to this game he don't quit for the fancy of money. The fact is he can't quit. Being a newspaper man is like being an infant in a cradle. It isn't your fault. It's something that has been wished on you that you can't help. You'll stay in the game unless your wife hankers for something that journalism won't provide. Then you will stay out just long enough to make the purchase. And pop! There you come back again."

Sullivan gently pulled a cord hanging from the shaded light over

his desk. Its illumination fell on half a dozen piles of typewritten

paper, lead weights, tissue and a pile of pencils. Out-doors the street lights were beginning to flicker and the chill of the mountains was

creeping down into the valley.

"Well," said Robinson as his eyes flashed victoriously. "how about

that red headed Hoosier?"

"Norman Walker?" interrogated Sullivan glancing over the top of

his glasses and shaking his graying hair. "He will he back. Fifteen years with the Associated Press down here on the border and in Mexico has him roped and tied like a yearling at branding time. He has known every Mexican revolutionary leader since Diaz was murdered. He has hobnobbed with bandits; been feted by presidents, and asked for advice when he went after interviews.

"He quit the game when Villa gave up gunning and accepted that three hundred thousand acre ranch at Canutillo, in Durango, from De La Huerta. No Villa, no news, he said and threw up the job!"

"Admitted," interpolated the other smiling, "and he is in the publishing business for the money not for the love of the stinking press room. No more danger of his coming back than there is of my being offered a street job in li'l' ol' Noo Y'rk, and you can figure for yourself how remote that is," vouchsafed the reporter.

KIDS VS. JOURNALISM.

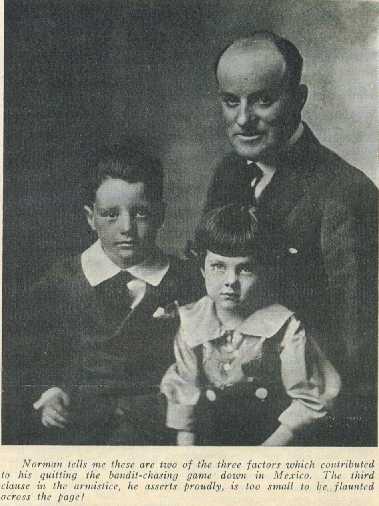

"If Walker never came back," asserted Sullivan pulling down his glasses so that he could straighten up his head, "I would he willing to bet my sedan against your shoes that his wife and those three red headed kids are the cause of it. Just wouldn't let him do it that's all.

"If they stay out they belonged to the boiler works to start with. Walker isn't that kind. But there are a lot of you young fries who think you belong when you don't. About all you kids know is how to follow a set routine of writing that says 'alleged' or 'announced' in every paragraph.

"Why this paper here has made more good hotel clerks in the last two decades than all of the colleges in Texas have made newspaper men. A sheep skin nowadays don't mean much. You know a lot about one thing and nothing about a lot of things. And a newspaper man like that isn't worth much.

"Now when I was a kid," Sullivan was saying as he shoved his thumbs into the arm holes of his vest, "they taught a fellow a little about everything and not much about any one thing. A fellow who succeeded in breaking into the newspaper game in those days had a good foundation to work from.

"This Walker fellow don't belong where he is. Writing books about Mexico don't have the thrill of edition time and it won't hold him. You watch. Just let some little thing break loose down in Mexico and you'll find Walker dashing off to the seat of the trouble about which none of the rest of us will know anything and delivering up a series of humming-bird copy that would make even a hardened old veteran of the game like me leap clear across the table to get it into linotype slugs.

"He's the fellow that can do it. I doubt if there is a white man living, reporter or not, who knows more about Mexico than that red headed Hoosier."

The city editor, who was round in the middle from long hours and long years in a chair and who was nearly bare where once had been an enviable crop of luxurious black hair, got up and leaned against the table.

"That red head boy drummed his way through college in an orchestra

back in Bloomington, Ind. You might say he beat education into his head with a drum stick. When Jim Stuart pulled out of Bloomington and went to the Indianopolis Star young Walker drifted down here on the border in a pair of peg top pants and a yellow straw hat to set off his freckles and firey top. He expected it would be easy pickings to rush into a mining camp where there were a bunch of ignorant Mexican peons working and grab the reins as a mining engineer.

"He didn't belong there no more than you belong in New York," Sullivan went on shaking his finger and straightening his back. "He was as bum a pile driver engineer as he was an Indian herder. He got fired because the Spanish he learned in college couldn't be understood by the Mexicans. When he was telling them to do something they thought he was cursing them and quit. That's how bad was his Spanish.

"He learned enough Mexican cuss words, though, to drive mules. But that red headed boy was no more fit for that sort of thing than was De La Huerta to he president. It's a good thing they fired him and it's a better thing that the E.P. & S.W. freight train he rode out didn't go any further than El Paso."

From across the Rio Grande came the musical, yet monotonous toll, of the monastery bells striking the hour. A clock, hanging in front of a bank down the street, sounded five deep metallic notes. The bustle of the street continued and night was settling over the valley where nestled the twin cities of foreign parentage; akin yet unrelated.

"I remember the day when the Hoosier walked in here as well as I do the extra we printed when the Titanic sank. He came in flourishing his college certificate and telling how he had been working down in the mines. I gave him a job myself and told him what I wanted was mining news and for him to name his own salary.

"Why you fellows who always are trying to get salary increases would doubt it but that Hoosier boy said he would be glad to get five dollars a week. That's what we agreed on and he paid his own salary the first week because I forgot to mention to the cashier that he was on the payroll.

"He didn't tell us he'd been fired from those mining jobs or probably we never would have had him working here. We thought he knew his stuff, that we were getting a chap who could write and who knew the mines. But then he made good in the long run. I sort of got tired drilling into his red head how newspaper English differed from college English but then he learned. As a matter of fact he probably violated fewer ethical rules in getting the novice shell off his back than any cub I've ever trained."

Sullivan always spoke in a drawl and now he was rolling his tongue in a constant sound with hardly noticeable pauses between his sentences.

"Now that's the point," Sullivan said sharply. "The training has as much to do with making a good newspaper man as it does with making a bad one.

"The training I gave that boy! And look at him now," he went on in the pride he felt was justified.

"It always seemed to me that some act of providence must have sent him here at that moment. He was just getting whipped into shape to write a fairly good news story when the Mexican revolution broke. It didn't seem like it would amount to much to start with," Sullivan went on slowly, "but I'll be darned if that red headed kid didn't discover that a Madero junta was going on right here in town, go to it secretly, get in and occupy the only chair in the house while Madero, Garibaldi, Raul Madero, Orozoco, and Eduardo Hay sat around on the bed laying their plot to overthrow the government.

"Walker made friends with every one of them even taking a chance

on getting killed because Madero was there disguised in a mother hubbard and sunbonnet while U. S. secret service men were hunting high and low for him. If they would have recognized him there would have been a lot of fireworks and Walker might have gotten his.

BIG SCOOP!

"That was a great Scoop for this old sheet. The federals got an idea somewhere that Walker belonged to that coup because he had attended the junta and wrote about it so ably in the Herald. So one day when he was out in the big sandy trying to reach a rebel camp the federals captured him, gave him a hurried court martial, and ordered him shot at sundown. Funny how he got out of that.

"While he was waiting to be shot he told a lieutenant that he had a couple of dollars and that he'd like to buy the officer a drink before

he checked out. The officer finally consented, saying that a fellow who

was doomed to die ought to have his last wish anyway. They went over to the cantina, and after a while the officer got mellow enough to do about anything Walker wanted. Walker, incidentally, had thrown his liquor into the cuspidor because he don't drink nothing more than water.

"Walker talked him into going before the commander of the garrison. That was a great sketch. By George! The Hoosier talked the old general, Juan Navarro, out of the execution, got a pardon, and was soon hurrying back to the border to write about it.

"Now that's just how the Hoosier made his second great scoop. All of the rest of the newspaper men who flocked down here from New York and Chicago kept close to the federal headquarters. Walker did not. Not by a damned sight. He went out in the field with the rebels, got the advance plans on attacks, and then hurried into the city to see the bombardment as an eye witness.

"It wasn't long before some of the big newspapers got next to the way the Hoosier was delivering the goods. He signed up to write for the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, and the New York Herald and he handed them hot scoops every day. Thee story he wrote on the attack on Juarez -- a peach of a piece of copy -- was copped intact by a cap-and-cane reporter from New York and sent to his paper verbatim. The reporter got a watch and a lot of praise for that steal. And I hope you won't ever tell anyone that I told you because I wouldn't like to have that little secret get home, see," Sullivan said winking.

The monastery bells tolled three times. The noises of the street were subsiding and the shouts of news boys were being replaced by the prancing music from the plaza across the river where Mexican boys and girls were walking in their traditional promenade around the square.

"Why when the federal troops were scouring the country for General Pascual Orozco, didn't this Indiana boy ride nearly a hundred miles up into the mountains and find him? He sure did; right through federal and rebel lines with only a wave of his hand in greeting when they ordered him to halt. And him, armed only with a pair of binoculars and one measly little six-shooter. Sure he found him. Found him at Carrizal, which had been abandoned; had pictures made of himself with the general to prove his discovery and then dashed back only to have some chump steal it right out of his hand. Rotten dirty trick!" exclaimed Sullivan bitterly.

"Every one of those bandits were friends of his. Why didn't Villa try time and again to have Walker get him a job as a section foreman on the Southern Pacific? He sure did. And then when Madero was assassinated Walker helped Villa get started down into the interior with six mules, a sack of flour and three hundred rounds of ammunition, to get revenge. And Walker was right there to greet him when Pancho Villa came marching back a short time later with thirty thousand well disciplined, trained and uniformed men and more artillery than the United States Army.

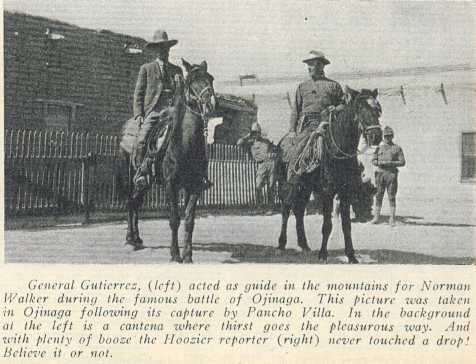

"That Red Headed Hoosier was the only white man that Villa trusted. And while Walker knew he was treacherous because of his uncontrollable temper he never feared him. Not even the time when he left the Pershing expeditionary forces which were hunting Villa in the hills back of Ojinaga. He got a whale of a yarn, sent it out exclusive, and then stood by while Villa captured the town. Another scoop! And the reason they were scoops is just like I told you a minute ago, Eddy, because all the rest of the news hounds were following Pershing instead of hunting for the source of the news.

PERSHING'S FRIEND.

"Walker and Pershing are real friends. Just like that," he went on holding two fingers close together. "Why Walker was the one who told Pershing that his family had perished in the Presidio fire at San Francisco. And he felt mighty bad about it but then he knew it was his duty to do it. Pershing never forgot that. When he came home from the world war he went right to Walker's house and bawled him out in the morning because he had got a more sumptuous breakfast than ham and eggs as the great general had ordered. That's a real guy, that fellow Pershing.

You remember when the American cavalry started out after Renteria who had captured two American aviators? That was about the time you came to work here. Walker didn't follow the soldiers like the rest of the newspaper gang. Nope! He had his own way of doing it and he put over a scoop a day with an extra one thrown in once in a while. He got an airplane, flew down into Mexico hunting for the lost aviators, and located Carranza troops marching against the American cavalry.

"That's not all!" Sullivan laughed as he recited the exploits of the Indiana reporter. "He beat poor old Wally Smith to the rescue of the aviators by swimming the ford at Candelaria at midnight to get the story moving. Walker told me half a dozen times that he ought to apologize to Wally for that. If you ever run across Wally Smith tell him, will you, Eddy?

"Sure that boy knows them all. He says Calles is a real man and that he will put a peace plan over in Mexico when he succeeds Obregon to the presidency in December. He says Calles is as hard as tacks, stronger than Flores, and not too much socialism in his politics to destroy his power to keep the country going.

"Obregon, too, was a strong personal friend of the Hoosier reporter,"

Sullivan was saying. "When Obregon went into the castle at the Bosque de Chapultepec he sent for Walker, and Mrs. Walker, had them to lunch and ordered a motion picture made of the event. Imagine President Coolidge, or Harding, or Wilson, sending for a reporter on a small town paper like the Herald here and dining him.

"He was a pal of Victoriano Huerta. When Huerta died out here at Ft. Bliss after trying to start another revolution and get the United States embroiled so it couldn't participate in the world war, he was on the verge of telling Walker the real story of how Madero was murdered. Huerta died with the words still in his mouth; the last vain wish of the old general unrealized. And Walker was one of the pall bearers who carried him to his grave. Huerta was a good old skate, at that," the city editor was saying as the monastery chimes struck the half hour.

"He was a good singer, had a fine tenor voice, and he liked to get

off in the corner with Walker when he was feeling safe from his enemies and sing. Huerta could sing as long as he had tequila sitting in front of him. And he often remarked how much like Caruso he was. As a matter of fact he looked like Caruso and his voice was, in truth, a lot like the great tenor's. He had a lot of American opera offers but he preferred to fight and he died with his boots on just as he wanted to die.

"After Villa got that ranch out in Durango for promising to behave himself, the bandit sent for Walker, dined him, and then asked Walker to write a scenario in which he would be co-starred with Bill Hart and Louise Glaum. Villa told him that an American producer had offered him fifty thousand dollars to appear in a picture and all Villa wanted with the money was to outfit three thousand soldiers he kept on his ranch for the picture. Walker wrote the scenario but the thing fizzled because the American movie people thought that Villa was no longer a head-liner." Sullivan went on glancing at his watch and rolling down his sleeves. "A newspaper man hasn't any business writing anything but news anyway!" he declared.

"Then came a hot one. The Chicago Tribune-Ford million dollar suit was being heard. Walker was called as a star witness. He spent a month reciting how he escaped being executed. How he had rescued a Colonel Navarro who had pardoned him and how he had won his liberty.

UNIQUE EVENT.

"That's pretty good, too," Sullivan was saying. "He's probably the only Associated Press reporter in history who broke into his own service with his own story for a column."

Sullivan was slipping his arms into the sleeves of his coat. The monastery chimes again were tolling and the street clock below the Herald's office window struck six times. The raucous noise of the home-going workers had subsided and across the river, in Juarez, the yellowish lights of the city flickered in the hazy distance.

"But there's one thing about that Walker boy," Sullivan said slipping on his hat. "He'll be back in the game because there's where he belongs. It's part of him just like it's a part of Jim Stuart. He's a part of it. A couple of pieces of machinery that are made to run on the same shaft are useless unless there is a wedge pin to connect them. That's the way Walker is when he's out of the game," Sullivan philosophized.

"But he's making money" protested Robinson. "Walker has quit the game. That fifteen years was enough for him--, for two men like him--," Robinson asserted.

"You're all wrong," Sullivan said heatedly.

There were footsteps in the hall that led to the editorial room stairs. Sullivan turned around to face the entrance and as he did a messenger emerged from the darkness.

Sullivan signed a yellow slip, handed it back to the boy, and opened the envelope. He read its lines carefully and with a smile handed it over to the youth.

"Mailed you four page interview with President-elect Calles tonight. Exclusive outline for reconstructing national political and financial system. Having dinner with him tonight and will get another story for you. Give it to the A.P., and tell my wife that business is detaining me for several days -- WALKER."

"What did I tell you, boy? That guy Walker may be running a publishing house, chasing down to Mexico City to get data for books he's writing, but.., but--, well, damn it all, he'll never quit the game because news pops wherever he happens to be. That's him all over!"

|